Why passive learning is an ineffective learning method

There is this persistent belief in the world of language learning that seeing a word a couple of times will allow the information to effortlessly sink in.

If you don't know anything about memory it might seem like a logical and tempting concept.

After all, the repetition is the mother of all learning.

Laying your eyes on some piece of information time after time should make remembering easy, right?

Not really.

Not that learning can't happen then. It can. It's just excruciatingly slow (read more about passive learning).

I would like to show you a couple of experiments which, hopefully, will help you realize that a number of passive repetitions don't have that much of influence on your ability to recall information actively.

Let's start with a great experiment which went viral recently.

Drawing logos from memory

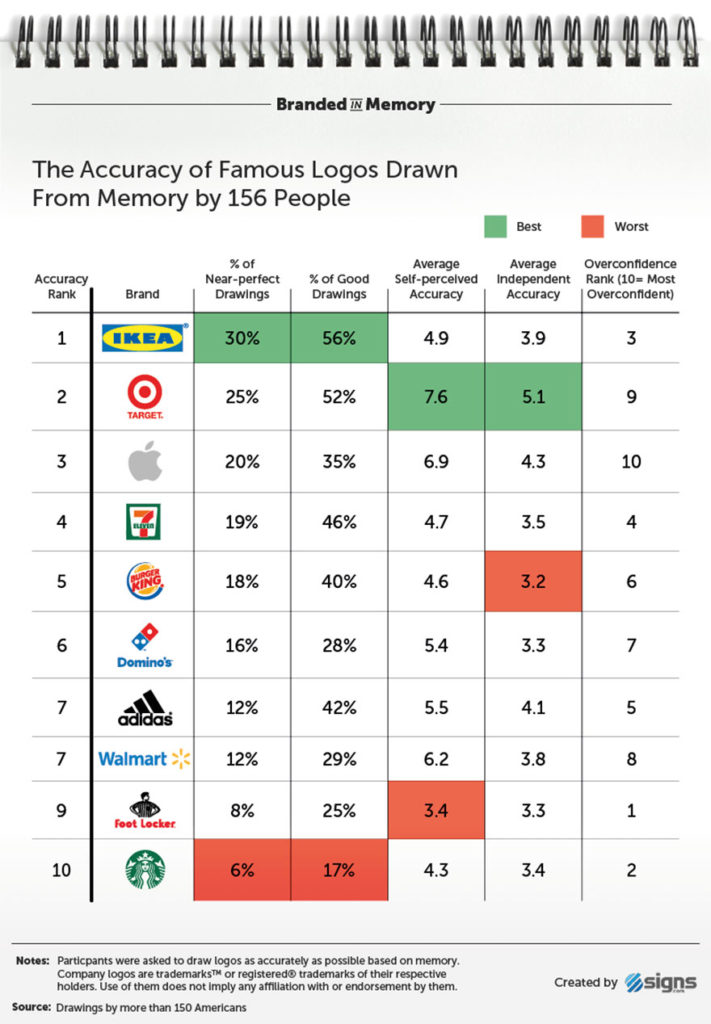

Signs.com has conducted a fascinating experiment, asking 156 Americans between the ages of 20 and 70, to draw 10 famous logos as accurately as possible. The only trick was, that they have to do it without any visual aids, simply from their memory (source - BoredPanda).

How did participants do?

Let's take a look at a couple of examples.

The apple logo, which one could argue is very simple, was somewhat correctly drawn by 20% of participants. If you are having a bad day, here are some of the less successful attempts.

The Adidas logo was correctly recalled only by 12% of participants.

Ok, I know that all this begs a question - what does it have to do with memory?

Implications of the experiment

The experiment's original intent was very interesting on its own. However, if you take a good look and prick up your ears you will soon discover that there is more to it! The experiment is trying to tell us something!

What's that, Mr. Experiment? What are you trying to tell us? - passive learning sucks!

Come again, please? - passive learning sucks!!!!

Now, why would Mr. Experiment say such a thing?

How many times would you say that you have seen, so far, Apple's or Starbuck's logos?

50? Don't think so.

100? Highly doubt it.

1000+ ? That's more like it.

It's a safe bet that an average participant in this experiments has seen each logo at least several thousand times. Several. Thousand. Times.

That's a lot, to say the least.

Let's look at their final results. Surely, with that many "reviews" they must have remembered logos quite well.

Don't know how about you but it's one of the sadder things I have seen in my life.

And I have seen a cute kitten getting soaked by the rain and crapped on by a pigeon.

But it's all good because there is a lesson or two in all that doom and gloom.

1) Retention intention matters

It wouldn't be fair if I didn't mention this - one of the main reasons why people don't remember information is that they are not even trying.

If you have a neighbor called Rick who you hate, you won't care much if he is sick. Rick can eat a d*** as far as you are concerned. You don't want to remember anything about the guy.

The chance of remembering anything if you have no intention of conserving that information is close to zero. It was clearly a case in that study.

Who is warped enough to deliberately memorize logos?

2) Number of passive repetitions has limited influence on our ability to remember

This is likely to be the most important lesson of all. Sometimes even dozens of repetitions of a given word won't make you remember it!

3) Complexity of information matters

If you look at the table, you will notice another interesting, and logical, thing. The more complicated the logo the less accuracy we could observe.

Arguably, Starbucks' logo is the most complex of them all. Not surprisingly it could only boast a recall rate of 6%.

It stands true for words as well.

The longer or the more difficult to pronounce a word is the harder it is to commit it to your memory.

Interestingly, some comments suggested that all those companies failed at marketing.

It is clearly not the case. Above all, companies aim at improving our recognition of their brands and products. And that we do without the slightest doubt.

Other experiments to test your ability to recall

The experiment conducted by sings.com had its charm. However, you don't need to make inroads into other areas of knowledge in order to carry out a similar study.

It's enough to look around.

1) A mobile phone test

According to comScore’s 2017 Cross Platform Future in Focus report, the average American adult (18+) spends 2 hours, 51 minutes on their smartphone every day.

Another study, conducted by Flurry, shows U.S. consumers actually spend over 5 hours a day on mobile devices! About 86% of that time was taken up by smartphones, meaning we spend about 4 hours, 15 minutes on our mobile phones every day.

It means that you take a peek at your mobile phone at least 40-50 times per day or over 10000 times per year.

Now a question for you - how confident are you that you would be able to draw your mobile phone without looking at it?

2) A watch test

It's safe to assume that if you have a watch, you look at it dozens of times per day. Most people hold their watches dear and carry them around for years. That would make it quite plausible that you have seen your watch thousands of times.

The question stays the same - how confident are you that you would be able to precisely draw your watch without looking at it?

3) A coin test

Yet another object which we tend to see frequently.

Choose a coin of some common denomination and do your best to replicate it on a piece of paper. Results might be hilarious!

What's that? Your curiosity is still not satiated?

Then you might design an experiment and run it to see how much you can remember after one hour of reading compared to one hour of learning actively some random words (i.e. using them in sentences),

Let me know in the comment about your results if you decide to run any of those tests!

Especially the last one!

Why is passive learning so ineffective?

1) You think your memory is extraordinary

This is an interesting assumption behind passive learning which you might do unconsciously.

You see your brain like a humongous harvester of information.

Wham-bam! You reap them one by one. The assumption, as beautiful as it is, is plain wrong.

Your brain is more like a bedraggled peasant with two baskets. There is only so much crap he can pick up throughout the day.

2) Brains want to forget

You see, your brain constantly works on forgetting most of the thing you come into contact with.

Reasons are simple:

- 1our brains are slimy and wrinkled assholes

- 2the goal of memory is not to transmit the most accurate information over time, but to guide and optimize intelligent decision making by only holding on to valuable information.

Why should your brain care about some words if many of them don't occur that often in everyday language?

3) No attention and no encoding

The simple memory model looks more less like this:

- 1Attention

- 2Encoding

- 3Storage

- 4Retrieval

The amount of attention you devote to a piece of information you want to acquire is almost non-existent. Just a glimpse and your roving eye is already elsewhere.

And since almost no attention is allocated to your learning, there can be no encoding as well (more about encoding here).

Passive learning and the illusion of knowledge

Did you know that research estimates that about 50% of the primate cerebral cortex is dedicated to processing visual information? That makes a vision the most important sensory system.

No wonder that our vision is the closest thing we have to the perfect memory.

In one of the most famous memory experiments of all times (1973), Lionel Standing proved that it is hard to rival vision in terms of capacity to retain information (Standing, L. (1973). Learning 10000 pictures. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 25(2), 207-222.)

Learning 10000 pictures

Lionel Standing, a British researcher, asked young adults to view 10,000 snapshots of common scenes and situations. Two days later he gave them a recognition test in which the original pictures were mixed in with new pictures they hadn’t seen. The participants picked out the original pictures with an accuracy of eighty-three percent, a jaw-dropping performance. - Robert Madigan - How Memory Works--and How to Make It Work for You.

Impressive, right?

Not exactly.

The thing is that this information is not something you know actively. You can recognize it but cannot retrieve it most of the time.

Don't get me wrong. Knowing something passively has its advantages and can be a really powerful factor in creative and thinking processes. But if you want to speak a language you have to know vocabulary explicitly.

Energetic nodding and grumbling worthy of a winner of the one-chromosome lottery don't count as a conversation.

Why passive learning makes us believe that we "know"?

In another famous experiment, memory researcher Jennifer McCabe showed why students think that cramming and reading are superior to studying by recalling (which has been proven time and time again to be a better learning method).

In the said experiment, students from two different groups had to read the same one-page essay.

The first group was supposed to recall and write down as much information as they could upon finishing.

The second group was given a chance to restudy the passage after they finished.

One week later both groups were tested on their memory for the passage. Not surprisingly, the second group crashed and burned. Its performance was far worse than the one of the first group.

What's more, students from the second group were actually quite confident that they would fare better.

"How could they be so wrong?", you might ask.

Most likely, they based their answers on their own experience. They knew that when they finished reading material over and over, they felt confident in their memory. The facts seemed clear and fresh. They popped into mind quickly and easily as the students reviewed them. This is not always so when recalling facts in a self-test—more effort is often required to bring the facts to mind, so they don’t seem as solid. From a student’s point of view, it can seem obvious which method—restudying—produces better learning. Robert Bjork refers to this as an “illusion of competence” after restudying. The student concludes that she knows the material well based on the confident mastery she feels at that moment.

And she expects that the same mastery will be there several days later when the exam takes place. But this is unlikely. The same illusion of competence is at work during cramming, when the facts feel secure and firmly grasped. While that is indeed true at the time, it’s a mistake to assume that long-lasting memory strength has been created. - Robert Madigan - How Memory Works

Illusions of competence are certainly seductive. They can easily trick people into misjudging the strength of their memory as easily as they can encourage students to choose learning methods that undermine long-term retention.

The best defense is to use proven memory techniques and to be leery of making predictions about future memory strength based on how solid the memory seems right now!

Final thoughts

As a long-life learner, you should understand that passive learning is one of the slowest ways to acquire knowledge. Adopting such a learning style creates the illusion of knowledge which further perpetuates this vicious circle.

The best way to approach passive learning is to treat it as a complementary method to active learning. The rule is simple - once you are too tired to keep learning actively, you can switch to passive learning.

Done reading? Time to learn!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 14 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.

Thank you, Sophia. I think it’s terrible. The only reason why people like Steve get away with this learning style is that he already knows many languages. That allows him to circumvent some of the memory limitations thanks to his background knowledge.

There are several musical pieces like Thaïs Meditation that I have never played or studied by other means, but which I almost know by heart just because I have heard them so many times. Now, for about 25 years, my brain did practice remembering pieces by heart (I remember them mostly by how they sound, I don’t “see” the sheet music in my mind and my muscle memory can fail, leading to improvised fingerings) so I do think Steve’s method might also work because he has been “training” that method. As I would think my brain shows more activity when listening to music than when looking at paintings, for example, even if I don’t consciously pay any more attention. If that makes sense?

Hi Natasha! No argument here that it’s perfectly doable. However, recalling a tune can’t be compared to passive learning. Using a language is a multilayer skill requiring many different subskills (pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, etc.). The only fair way to compare music to language would be to say that after listening to a song lots of times you can play it on an instrument without (any) bigger problems. And I don’t know many musicians who can pull it off.

As for Steve, I can repeat once again – working memory is modulated by long-term memory. Any person with knowledge of many languages will be able to utilize passive learning way more effective than your average Joe. Even more so if their target language is similar to the languages, they already know. Still, that can hardly be used as an argument for the effectiveness of passive learning.

Hello Bartosz! Very nice to see that you actually respond to comments even if the post is old! I actually personally know several musicians who can sight read almost anything for their instrument (and I could probably play Thaïs quite well , too, as it is not that difficult), but it does require that they are already very proficient at the instrument. So yes, I agree that your average Joe would not be able to do that and I was not trying to say that passively learning languages would work for the average Joe either, even if it works for Steve, just thinking about why it might work for him.

Of course, I do! Here we are not even talking about sight-reading music but hearing the melody and playing it back. Although the effect is basically identical to what you have said. Professional musicians can certainly do it and Steve can be definitely likened to them in his field of interest 🙂