The Magnet Theory – Why Deep Understanding and Problem-Solving Starts with Memorization

The quality of your life depends mostly on your ability to make the right decisions and to solve problems.

One could think that in the world of almost unlimited access to information our decision-making abilities should be getting better and better.

Is it really the case?

I don't think so. There are many explanations for why it is so.

However, instead of delving into them, I would like you to show you how to improve the quality of your thinking and problem-solving skills with the concept of my own devising - The Magnet Theory.

But first things first. Let's start with a structure of knowledge.

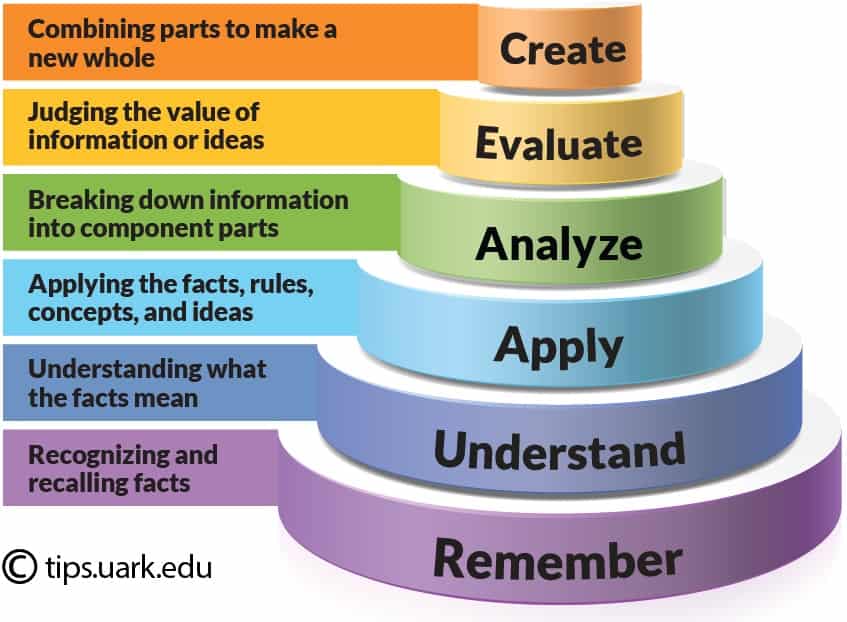

Bloom's Taxonomy - the Hierarchy of Knowledge

Not a week goes by when I hear someone say - if you don't understand something, don't learn it. And some part of me crumbles away every time when I hear it.

Why?

Because nothing could be further from the truth.

Understanding is very often the by-product of all the information at your disposal.

Let me explain why. Let's start with fundamentals i.e. Bloom's taxonomy.

Bloom's taxonomy depicts the structure of knowledge and how it is organized.

Take a look at the foundation of this pyramid. Can you see it? That's right. Understanding doesn't seem to be the most important element of knowledge.

Why do you think it is so? I will tell you why - because you can't think without facts.

Facts are frequently the foundation of good solutions and thinking.

Why Understanding Is Overrated

My guess is that most of the time, on the surface, it is easier to understand something than to memorize dozens of different facts.

We like to assume that if A leads to D then it surely happens in a nice progression - A causes B. B causes C. C causes D.

The reality is that most of the time progression looks more like this.

A -> L -> B -> G -> C -> K -> X -> E -> D

It's an interaction of dozens of different elements which we very often don't see because of our limited knowledge. This phenomenon is called "The illusion of explanatory depth".

"People believe that they know way more than they actually do. What allows us to persist in this belief is other people. In the case of my toilet, someone else designed it so that I can operate it easily. This is something humans are very good at. We’ve been relying on one another’s expertise ever since we figured out how to hunt together, which was probably a key development in our evolutionary history. So well do we collaborate, Sloman and Fernbach argue, that we can hardly tell where our own understanding ends and others’ begins."

“This is how a community of knowledge can become dangerous,” Sloman and Fernbach observe.

The Real Reason Why Understanding Starts With Memorization

As you probably know, your short-term memory is the bottleneck in the learning process. It can only accommodate a couple of pieces of information at the same time.

That doesn't inspire much confidence comprehension-wise, does it?

How many concepts do you know that can be understood by knowing just 3-5 facts? I can tell you right away, that there are not many of them. And even if you find any, they probably won't be worth your while.

In order to see the big picture, you need a lot of facts. Which, truth be told, can be problematic.

Why?

Because you don't know how many puzzle pieces are needed to create it. That leaves you just one choice - you have to keep on memorizing things even if they don't make any sense at the moment. You need to memorize facts before you understand what they mean.

If you memorize just the things you understand, you will never be able to look beyond the obvious. The problem nowadays is that almost nobody is willing to do it. Why bother if all the knowledge you need is at your fingertips?

This phenomenon is known as the Google effect or digital amnesia.

It is the tendency to forget information that can be found readily online by using Internet search engines such as Google. According to the first study about the Google effect, people are less likely to remember certain details they believe will be accessible online.

The thing is that if you want to be the best at something, you need all those pesky details.

My process of knowledge acquisition

Throughout the years of running this website, I have received tons of questions about my process of writing and thinking (e.g. The truth about the effectiveness and usefulness of mnemonics in learning).

My answer has always been the same and possibly disappointing to others - I try to memorize everything.

I don't care how abstract or vague a given piece of information seems. I will commit it to my memory.

I do it because I can't possibly know which fact will tip the scale and raise the curtain to reveal the magnificence of understanding.

That's why I can't be picky.

At some point, the facts always come together to form a clear answer. Sometimes, you just have to wait for it.

For example, right now I can tell you quite exactly what science currently has to say about the process of working-memory consolidation. This knowledge includes even tiny facts about frequencies of different brain waves.

And I will be honest with you. I don't know right now the purpose of this information. I am more than clueless. But I am pretty sure it will come handy one day. Maybe in one year, maybe in ten. Whenever it might be, I know that I will be ready.

It might not be the most pleasant way to acquire expertise. However, it's sure as hell the fastest and the most certain way to do it.

The Magnet Theory - How to Understand the Process of Effective Thinking

Years ago, I was obsessing over the question - how come two smart individuals can arrive at completely different conclusions?

I knew that asking good questions was important in that process. I also understood that you couldn't think effectively without facts.

The effect of these cogitations turned into something I dubbed The Magnet Theory.

It's a very elegant way of understanding the process of problem-solving and effective thinking.

Think of any question or problem you might have as a powerful magnet. The minute you encounter some riddle, the magnet starts doing its magic. It starts scouring your mind and attracting everything which might be useful in the process of cracking a given problem.

And I really do mean everything - anecdotes, scientific facts, your personal experiences and so on. The whole comes together and creates a solution to the problem.

There is one more component of the magnet theory - your ego. It filters and potentially distorts all the potential conclusions you may reach. Even if all the facts are in favor of one solution, your ego might nudge you to reject them all.

The Consequences of the Magnet Theory

1. Almost everyone has an opinion

How many people do you know who don't have an opinion on some matter? Not many.

That's the thing. Any question you ask or problem you state is a potential magnet for the mind of your interlocutor. The magnet will scrape up every little bit piece of information. As a consequence, this motley clue of assorted facts and anecdotes will form an opinion on a given topic.

Are these opinions worth much? You can answer this question yourself.

2. Your thinking is as good as the information you remember

Remember that you will always have an answer to almost every question. That doesn't mean that the answer you come up with is any good. As the great and late Richard Feynman used to say

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.

Don't rush to the conclusions. Before you make a decision ask yourself this - how many good facts do I have at my disposal? Not opinions, not anecdotes but the cold scientific facts.

If the answer is "not many" then do your research to give your magnet some "better food".

I routinely distrust anyone and double-check any kind of information myself. Maybe I am paranoid but my behavior is driven by one simple question - how many people appreciate the importance of memorization and treat it as an indispensable part of their expertise acquisition?

The answer is - close to zero.

That automatically renders most of the opinions you will ever hear in your life invalid. Or at best they might be classified as half-truths. It sounds callous but it's definitely true.

Surveys on many other issues have yielded similarly dismaying results. “As a rule, strong feelings about issues do not emerge from deep understanding,” Sloman and Fernbach write. And here our dependence on other minds reinforces the problem. If your position on, say, the Affordable Care Act is baseless and I rely on it, then my opinion is also baseless. When I talk to Tom and he decides he agrees with me, his opinion is also baseless, but now that the three of us concur we feel that much more smug about our views. - Why Facts Don't Change Our Minds | The New Yorker

3. Your ego can be the end of you

It's worth keeping in mind that the more somebody holds himself in high esteem, the slimmer the chances that they will be swayed by facts that contradict their opinions.

What's worse, everyone is affected by this bias. Especially all the people who think of themselves as experts or have fancy titles like a Ph.D. or a professor.

Alas, the titles don't mean diddly-squat if you don't have vast knowledge.

If I invited you to a blind taste test of a $12 wine versus a $1,200 wine, could you tell the difference? I bet you $20 you couldn’t. In 2001, Frederic Brochet, a researcher at the University of Bordeaux, ran a study that sent shock waves through the wine industry. Determined to understand how wine drinkers decided which wines they liked, he invited fifty-seven recognized experts to evaluate two wines: one red, one white.

After tasting the two wines, the experts described the red wine as intense, deep, and spicy—words commonly used to describe red wines. The white was described in equally standard terms: lively, fresh, and floral. But what none of these experts picked up on was that the two wines were exactly the same wine. Even more damning, the wines were actually both white wine—the “red wine” had been colored with food coloring. Think about that for a second. Fifty-seven wine experts couldn’t even tell they were drinking two identical wines. - I Will Teach You To Be Rich by Ramit Sethi

Example 1 - Vitamin C

It reminds me of a great story. A couple of years ago, there was a lot of controversy in Poland around the man called Jerzy Zieba. What did he do, you might ask?

He wrote the book called "The Hidden Therapies - What your doctor won't tell you". It shook the medical world in Poland to the core as it exposed incompetence and rigidness of the Polish health care. In one of the chapters, he described wonderful qualities of Vitamin C which can be used among others to:

As a result, the real shitstorm ensued. He was publically flailed and tarred and feathered at the altar of science. There were literally thousands of medical professionals who mocked him to no end.

After all, he was not a doctor. So what that in his book he quoted hundreds of scientific studies from all over the world to back up his claims. He was no one and had no say in the matter.

I saw professors of medicine and oncologists saying straight to the camera that this is scientific tosh and they haven't seen even one scientific paper who proved it.

So why I am telling you all this?

Because each one of these detractors was dead wrong. There are actually hundreds of scientific studies proving the efficacy of vitamin C in treating almost every possible malady.

This anecdote is especially important for me because I have been personally interested in medicine for a long time now as it's definitely one of the main fields of knowledge where you are only as good as your memory. Throughout the years I have read, gathered and memorized dozens upon dozens of articles and studies about vitamin C which confirm its effectiveness.

In the end, the professors were wrong. The ego got the best of them.

It's an important reminder for all of us to never get too cocky. In other words - be humble or be humbled.

Example 2 - Losing Weight

Let's ponder over the following problem. Let's say that your aunt Elma wants to lose weight.

She has been buying Vanity Fair for a long time, so she knows that even though she accepts herself, she is fat and hideous, and needs to slim down.

The years of reading have equipped her with a truly powerful, intellectual toolkit.

She knows that she has to:

Is losing weight really that simple?

It might seem so. After all, doing all those things takes us from point A to point B.

Before, I move on. ask yourself the same question. Be sure to follow the whirlwind of incoming thoughts.

Can you feel how they are trying to organize themselves? Or do you maybe feel like you have a ready answer?

I can bet that your first instinct is to start spewing out all the facts in your head. I know that it is typically my first reaction.

However, what's on the surface might be merely a tip of the iceberg. But only once you take a peek "under the hood", will you be able to see the real complexity of the issue at hand.

If you want to lose weight, you have to:

Of course, it would be just the beginning of your investigative journey. Next, you would have to learn what is responsible for each of these functions.

Only then will you be able to truly understand what is required to lose weight.

And it would be a truly amazing journey because the truth is that there are thousands of possible solutions. If you dig long enough, I am sure you will be able to find the optimal one.

Do we have to understand all the things deeply?

I don't mean to make you paranoid. Of course, you don't have to possess a profound understanding of everything. Although I would suggest you do it for every area of knowledge which is of interest to you.

The Magnet Theory - Summary

The Magnet Theory is an easy way to understand how the processes of thinking and problem-solving work. It can be summarized in the following way:

The theory leaves us with three conclusions that are applicable to every area of life.

There you have it. I hope that you will be able to apply this theory to improve your quality of thinking.

Do you have anecdotes where some tiny piece of information helped you understand something? Please let me know in the comments.

Done reading? Time to learn!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 12 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.

H! I’ve skimmed his article on incremental reading, and it looks highly interesting, saved to read it more in-depth later 🙂 So it doesn’t actually seem like he has changed his mind regarding this topic. For example, here is a quote from the article:

“You MUST NOT memorize material that you do not understand! There is some hope that by doing more learning in other areas you will at some point understand. It is far more likely though that you will build up frustration with items that mean little. If you do not understand a term or concept, you need to dig deep into why. Is it terminology? This can be easily investigated and fixed. Or is it a problem with the material itself? Perhaps you can find an alternative on the net? Perhaps you can find a nice picture on the net to illustrate the item? Obviously, each little investigation takes time, but it is better to master 10-20% of the material well, that to cram an encyclopedia without comprehension.”

I think what he wants to say, is that without understanding a given concept you wish to memorize it’s much more difficult to encode it and integrate in the bigger picture. He does mention that understanding is also an incremental process, and that it’s important to build a good foundation before proceeding to more advanced information. So basically, with incremental reading you don’t need to understand the big picture, but start with memorizing the facts you understand, and build up on that. And if some information is incomprehensible, you should make an effort to change that, either by finding a better explanation or illustration/visualization, by providing additional context, or by looking if foundation knowledge is missing, in which case it’s better to postpone learning it until the more basic knowledge is in place.

After some extra googling I’ve also stumbled on a more recent article, where he elaborates a litte more on this rule and talks a bit about learn drive and the importance of making learning pleasurable: https://supermemo.guru/wiki/Do_not_memorize_before_you_understand

What a fascinating topic! 🙂

I think I might have directed you to the wrong article. I remember that he has written somewhere that he doesn’t see it as a set-in-the-stone rule.

And I agree – yes, understanding is extremely important. However, my argument is that if you want to achieve a profound understanding, often you need to rely on memorization as our short-term memory is very limited. Let’s be honest, a handful of facts that we can hold in our brains temporarily, are hardly a good basis for the level of comprehension I have in mind. As a result, tons of people cling to a couple of facts they remember and give their version of understanding that is often seriously lacking or just plain wrong. Look at the cholesterol debate in the world of nutrition. That’s a topic that requires literally hundreds of pieces of information to grasp relatively well. Yet, just a couple of arguments are brought to the table by any party once the topic is brought up. The same goes for mnemonics. They insist that mnemonics are great because they envelop actives encoding, etc. at the same time ignoring the fact that almost all the information is activated contextually; something that mnemonics can’t provide us with. That’s what you get when you try to understand based on a couple of pieces of information. And yes – it is fascinating! 🙂

Excellent post, lots to think about. I’m curious, what is your opinion of this article written by Piotr Wozniak? https://www.supermemo.com/en/archives1990-2015/articles/20rules

It appears to be highly recommended by many experienced users of SRS programs, and looks like a great aid in learning how to use such software effectively. But the first two rules (“Do not learn if you do not understand” and “Learn before you memorize”) seem to be in disagreement with your article, and I find it hard to reconcile the two opinions. I wholly agree with your arguments, yet the examples provided in “Twenty rules of formulating knowledge” and the argumentation against them also make sense, thus leading to a slight cognitive dissonance. 🙂 I’m wondering if it’s more an issue of semantics and so what appears to be a disagreement is actually not?

Thanks!

It’s one of the best articles on learning on the internet. I know it well. Piotr is also one of the best memory researchers that have ever walked the earth.

Having said that, if you read later pieces written by Wozniak (e,g., incremental reading), you will learn that he has changed his mind about learning when you don’t understand. I could hardly understand why he claimed it in the first place because of many counterarguments that one could quote. Either way, I am overjoyed that we are currently of the same opinion on the matter 🙂

Wow, it’s like a breeze of fresh air to read a well-reflected and philosophical post like this !! I wish more people thought like this way.

The only thing, I have a slightly different stance on, is that there are certain topics I choose to not spend mental energy on committing to memory in order to lower the load on my memory. Most of these topics, I do make a mental note about looking into later (such as health) if they interest me. I’m still aware that simply making this note also serves as a memory hook.

I wish I had a good anecdote of when random knowledge has helped me solve a puzzle. The only thing I can think of are a couple of lessons my mom taught me about compassion, such as “always consider how other people feels about what you say” – they turned out to be great eye-openers when I later remembered them (and enabled a much deeper empathy) 🙂

You’re absolutely right. We should know what not to spend our mental energy on. Way too often I tend to go over-the-top and memorize too much.

That’s still a great anecdote. Thank you for sharing!

Great post.

A lot of what you’re talking about used to be called ars combinatoria (the art of combination). People had lists of questions and associations they would make for both memory and understanding.

Ramus and Bruno are the big figures here, but we don’t actually have Bruno’s work on the art of combination through questioning and connecting. Hopefully it will surface one day if it survived.

Hi Anthony! Great to hear from you:) I didn’t know that this is the name of the method. I read somewhere about it a couple of years ago but the author couldn’t remember the source of this information either! I will look into it.