It’s time for part two of my miniseries on optimizing your learning! If you haven’t read the first part – click here. This time I

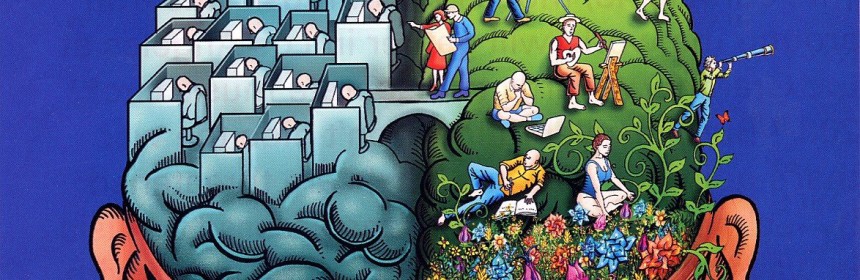

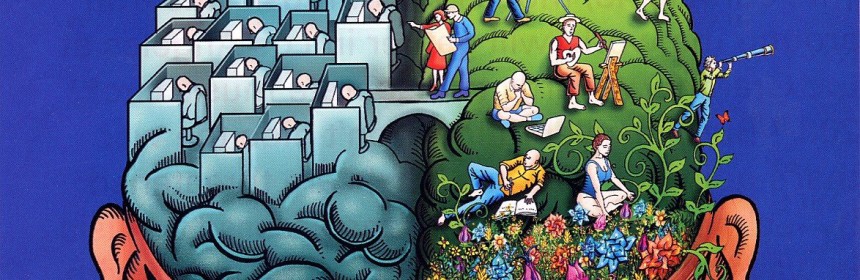

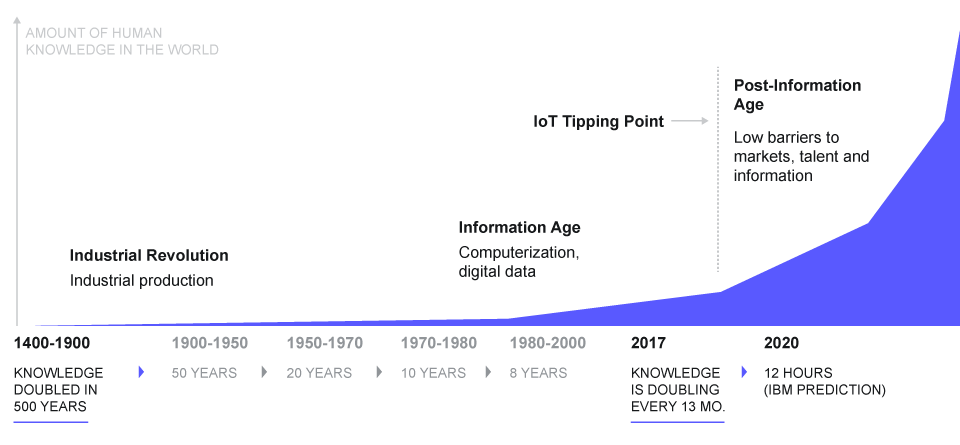

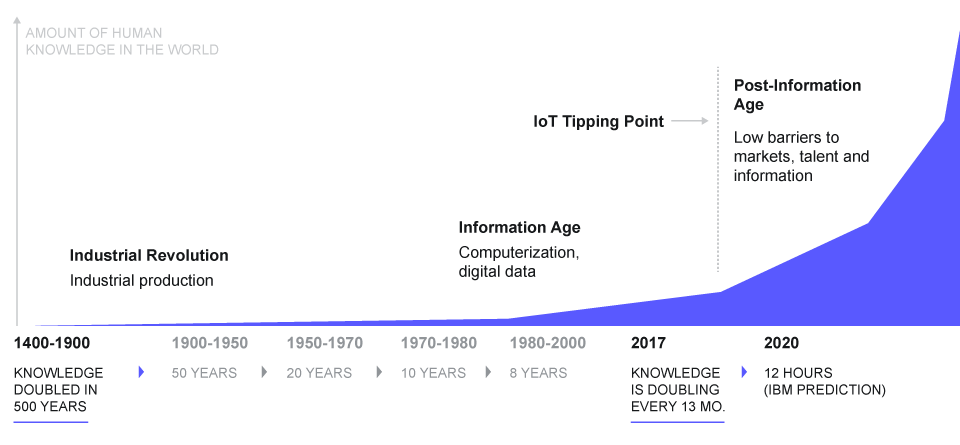

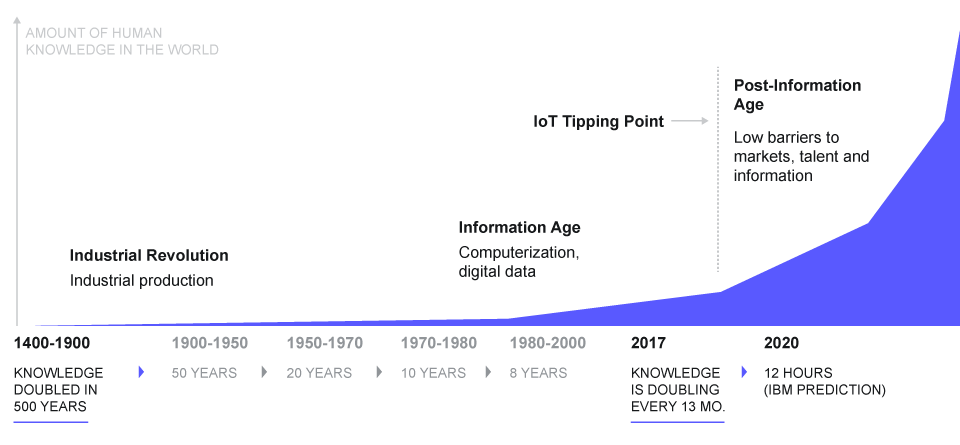

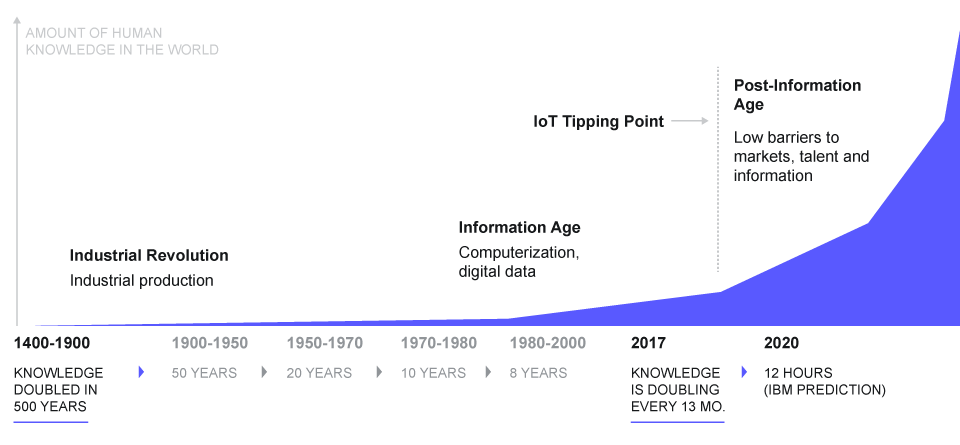

I love how paradoxical the modern world is. You are just a click away from accessing almost every imaginable piece of information ever created. If you could acquire just some of it, you would be able to dominate almost every possible area of life. However, it seems like there is a glass wall holding you back. You can lick it all you want but you can't get through it.

My guess is that most people are notoriously bad at tying information together. What's more, we are also easily overwhelmed by the sea of information. All the facts that we face usually take a form of an impenetrable tangle.

In this article, I would like to show you a way out of this maddening maze. It's not a complete map but it should be enough to help you wrap your head around any discipline. With some time and dedication, of course.

The remedy is a method of mine which I dubbed course-oriented thinking. Not only will it help you to create or consolidate your expertise but it'll also, hopefully, give you lots of ideas on writing a book or a course.

Knowledge coherence, or in other words the way we structure information we acquire. And we suck badly at it.

Throughout our entire education, everything is served to you on a silver platter. It's always the same dish - the prechewed and predigested informational spaghetti. God forbid that you put more effort into your learning than it's necessary.

And then comes the day when you need to recall and apply all this knowledge. You reach for emptiness. There is nothing there.

After all, the knowledge presented to you was structured.

The answer is "Easy come, easy go".

Learning takes effort.

There is no way around it. It doesn't matter how many people you will meet on your path who scream otherwise. You need to put in a lot of effort.

And let's be honest here. If you receive knowledge in a form of a fully digested pulp, you won't know how to use it. You won't understand it either.

The truth is that nobody can structure and organize your knowledge for you.

And this is where course-oriented thinking enters the scene.

In the simplest of terms, course-oriented thinking is based on one principle. You should approach every domain you want to master with a single goal in your mind.

You will create a course to teach someone all there is to know about a given subject.

It will be the best damn course in the universe on a given subject which you can sell to others (read more about mastering many fields of science here).

Pay attention to the words I have used.

It's not going to be any course. It will be the best in the world. No other course will come even close. However,

keep in mind that your course won't be any good in the beginning. Being the best is the end goal. It's a journey.

Initially, it will rather resemble a steaming pile of manure. With time, however, you will turn into your own version of David Statue. The one made of marble, not s**t. I better add it so there is no misunderstanding here.

If you want to go in, go all in. Create a course which will teach you every aspect of your field of choice.

Keep in mind that the course should be able to teach a complete beginner how to master a given field of science. If you want to teach somebody how to invest, even a retarded, three-headed shrimp which survived a nuclear apocalypse will succeed.

Ask yourself this while working on your project - "How can you make a layman understand what you want to convey?".

Another important assumption is that you're going to sell it. Of course, it doesn't really matter whether you do it or not. What matters is that this approach will give you some mental incentive to devote as much attention to it as it's needed.

You wouldn't sell people crap, right? Exactly. This way of thinking should help you keep your focus on the right track.

Another self-evident advantage of this rationale is actually creating something of value. You might be doing it for yourself right now. However, as the time goes by, you might be struck by a curious thought, "Why won't I create an actual course or a book?". And come it will. Trust me.

I still remember my bewilderment in college every time I saw an author publish a book. I couldn't grasp how it's possible to amass such vastness of information, structure it, and package it as a complete product.

The secret seems to be disappointingly easy. You start with a product in your mind and you learn as you create it.

If you set off on this journey with an intention of just copying a curriculum of already existing courses, you might as well stop reading right now. The course has to be your creation. Sure, you might borrow different concepts, methods or solutions from other authors in the field, but it has to be yours. Only this way will you be able to fully understand the scope of a given domain. Trust me, knowing how most of the puzzles fit together is amazingly empowering.

It also means that you can add whatever you want to the course. Dollop some funny pictures or a bucketful of ridiculousness on top of each module. Appreciate all those little peccadilloes that only you can bring to the table.

In my "investing course", I find myself frequently quoting a lot of prominent figures from the investing world. Sometimes one quote is more than enough to help a give rule to sink in.

Here is the one by Warren Buffet which I use on a daily basis:

"The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient."

Sure, I also include some scientific data to back up this idea. However, I don't find it even half as powerful as the aforementioned quote.

If you are new to some area of expertise, you may find it extremely difficult to create any curriculum. After all, what do you know?

Don't worry. You don't have to do all the heavy lifting on your own. Simply pick up any book, or google an online course which is similar to the one you want to create and copy its rough outline.

I would like to remind you that it's just a place to start. You shouldn't copy everything. Without the effort of creating a schedule, you won't be able to learn nearly as fast.

If you already possess a wealth of knowledge about some domain, you're in a great place. You already did the bulk of work in the past. Now, muster all you know and start structuring it from A to Z.

Typically, you should structure your course in an old-fashioned way. Break down a domain of your choosing into modules and units.

Remember that you're the structure of your course is not permanent. It's a living organism. The more you know, and the more information you add to it, the more it will change.

Don't get too attached to its current form.

By that point, you should already have a rough curriculum in place. The next important question you have to answer is, "how can I learn more about this"?

Actually, saying it's important would be an understatement. It's absolutely crucial. You don't want to learn from source you don't trust.

I might be old-fashioned but if I wanted to learn more about investing I wouldn't take advice from a pimply teenager who lives in his mom's basement. Especially if he has no previous track record.

Keep in mind that just reading information is not enough. You actually need to memorize it to be able to connect the dots.

Read more about the importance of memorization here: The Magnet Theory – Why Deep Understanding And Problem-Solving Starts With Memorization.

Don't take facts or information at face value. Pay attention whether the opinions are rooted in anything trustworthy.

As a rule of thumb, my bullshitometer buzzes like crazy anytime I hear that "there is a study proving ...", or better yet, "everyone knows that ...".

Have you read this study yourself? No, not an abstract, an entire study. If not, remain skeptical. As yet another rule of thumb, anyone quoting documentaries as a source of knowledge, especially about health-related issues should be slapped six feet deep into the ground by the mighty gauntlet of knowledge.

Sometimes I waive this rule temporarily if I respect a given expert enough. However, that's an exception.

I know what you're thinking. It's hard. And I fully agree. Nobody said that forming your own opinion and knowledge is easy.

It's confusing, I know. Can you be critical and open-minded at the same time? You can, and you should be.

The principle is best encapsulated by Stanford University professor Paul Saffo.

Strong opinions loosely held

At no point in time will you have a complete picture of a given domain. Hence, you are bound to hear lots of different opinions and theories which might contradict your present knowledge.

Don't discard them just because they don't sound right. Analyze their conclusions. And don’t stop there. Analyze the rationale which led to those conclusions as well.

A great example is a way in which I approach rapid language learning as described in a case study of mine.

After learning and analyzing hundreds of linguistic studies and memory-related books and papers, it wasn't hard to see why a typical approach can't work well. What's more, it wasn't too difficult to see why extensive reading and other passive learning approaches are usually terrible ideas. Yet, a couple of years ago there weren't many people who shared this belief. Luckily, language learning is one of those fields where usually results speak for themselves.

If I encounter some evidence which is either flaky or contradictory to what I already know, I still try to place it somewhere in the course. However, I always place an extra note saying "to be verified".

You can choose to copy my methodology or think up some other way to mark uncertain information. Whatever works for you.

Upon doing so, you are left with two choices. You can either set off on a revelatory journey to discover what the truth in this particular case is, or leave it for time being. As you acquire more knowledge, the problem will most probably sort itself out.

In my book, there is only one clear winner - Evernote. It's everything you will ever need to write a book, a course or anything else for that matter.

Of course, I might be biased as I don't know many other programs of this kind.

Evernote makes it very easy to create module and units for every single folder (i.e. your course idea).

If you have ever dreamt of mastering many fields of expertise, course-oriented thinking should also be right up your alley.

Once you read this article, you can download Evernote right away and start creating course outlines for every single domain that interests you.

Will you be able to pursue them all at the same time with smoldering passion? Definitely not.

Will you be able to work on them for years to come until you achieve mastery? Absolutely.

You can think of every field of expertise you want to master as a journey. Maybe you won't make too many steps in the forthcoming months. But you will keep on going and you will keep on getting better.

What's more, the mere awareness of having a course which you can expand should keep your eyes wide open to all the wonderful facts and information you stumble upon.

They all will become a welcome addition to your creation. And as with learning intensely, the more courses you create, the easier it will be to master any other domain.

I am pretty sure that you already have a rough idea of which areas of expertise you want to explore. Regardless, I've wanted to show you some examples of the courses I have created so far. Of course, they are work in progress. Knowing me, I will keep on expanding them till the day I die. You might use them as a source of inspiration.

The list is certainly not complete but it should give you a general idea of what to gun for. Remember to think long-term. Your course (i.e. knowledge) doesn't have to be perfect from the get-go. The mere action of having such a project in place will help you put any piece of information in the right context.

Approaching learning in this manner can lead to truly spectacular results. You might discover that after some time, some of your projects will come to life and will become an inseparable part of your existence.

For example, I have never thought of myself as an investor. However, just a couple of weeks upon creating a rough curriculum of my investing course, I dipped my toes in the financial waters. Surprisingly, it turned out that I am really good at it. These days trading is a part of my everyday ritual.

So what do I think? I think you should give it a shot.

One of the most important factors affecting your ability to remember things is the coherence of your knowledge. Course-oriented thinking can provide you with an excellent framework for structuring your knowledge. What's more, your potential courses can turn into real-life products which might benefit you in the future.

Keep in mind that your projects don't have to be perfect from the very beginning. They will probably suck. Only working on them systematically and methodically can guarantee that they will become world-class products.

Don't treat them dead-serious and don't be too formal. Sprinkle them with silly memes, anecdotes or quotes. Your courses should be a natural extension of your character. Let your personality shine through the quality information. With time, you might be truly surprised how much this approach can change your life.

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 23 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.

It’s time for part two of my miniseries on optimizing your learning! If you haven’t read the first part – click here. This time I will show you how to optimize your repetitions.

People like to see effective language learning, or any learning for that matter, as something mysterious. The opposite is true. There are just a couple of essential principles which you should follow if you want to become a quick learner.

Don’t get me wrong – effective learning gets more complicated; the faster you want to learn. And the more long-lasting memories you want to create.

Still, these principles can be applied by anyone, regardless of his sex, or age because the very little known truth is that we all learn, more or less, the same.

Forget about learning styles – they do not exist. I know. It sounds shocking. And it is probably even more surprising than you can imagine – one study showed that 93% of British teachers believe it to be exact!

But you and I, my friend, are not glittery and special snow-flakes. There are rules. And they are not to be treated lightly.

Let’s dig in.

Below you can find my list of the essential rules affecting your language learning progress. It’s far from being complete.

There are other rules and limitations, but the ones below are one of the easiest ones to implement.

To maximize your learning, you should make sure that:

If you only concentrate on reading and listening, you won’t get far. Your brain is terrible at memorizing things that you encounter occasionally.

Why?

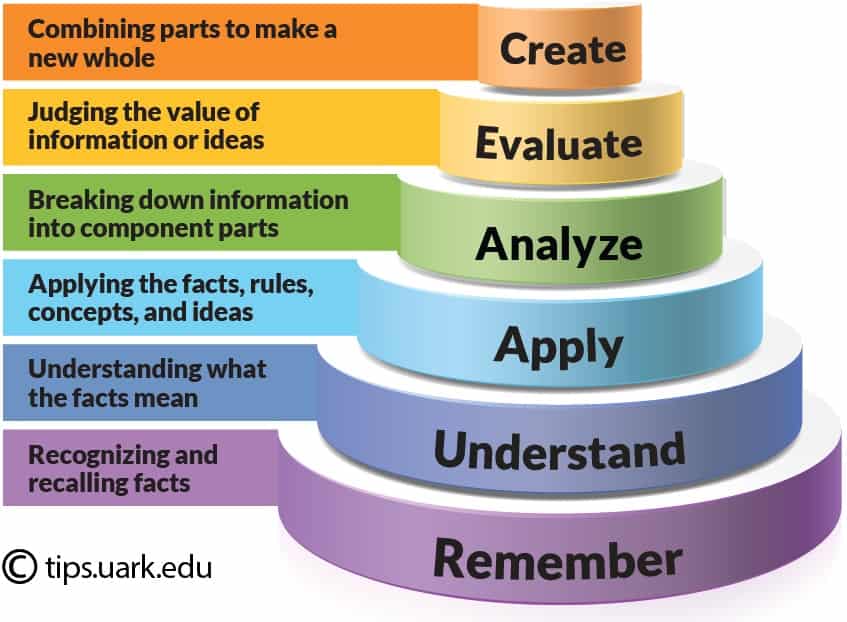

I will get to this in a moment. But first, let’s start with basics – the process of memorizing can be depicted in the following three steps.

1) Encoding – involves initial processing of information which leads to the construction of its mental representation in memory

2) Storage – is the retention of encoded information in the short-term or long-term memory

3) Recall – is the retrieval of stored information from memory

As you can see, the first step in this process is encoding. I can’t stress this enough – if you don’t encode the information you learn, probably you won’t retain it. You should always, ALWAYS, do your best to manipulate the data you try to learn.

Let’s try to prove it quickly.

If I told you right now to draw the image of your watch, would you be able to do it? Would you be able to reproduce the exact look of the building you work in? Of course not, even though you come into contact with these things multiple times per day.

You do not try to encode such information in any way! If the human brain were capable of doing it, we would all go crazy. It would mean that we would memorize almost every piece of information which we encounter.

But this is far from the truth. Our brain is very selective. It absorbs mostly the information that:

a) Occurs frequently in different contexts

b) We process (encode) –in the domain of language learning, the simplest form of processing a given piece of information is creating a sentence with it

c) Is used actively

One of the best ways to optimize your repetitions is by using SRS programs. But what is Spaced Repetition?

Spaced repetition is a learning technique that incorporates increasing intervals of time between subsequent review of previously learned material in order to exploit the psychological spacing effect.

Alternative names include spaced rehearsal, expanding rehearsal, graduated intervals, repetition spacing, repetition scheduling, spaced retrieval, and expanded retrieval.

How does the program know when to review given words?

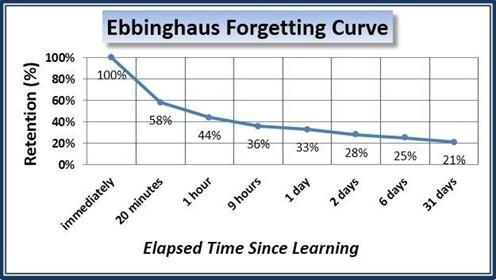

Most of such programs base (more or less) their algorithms on Ebbinghaus forgetting curve (side note: it has been replicated many times in the last 50 years)

The curve presents the decline of memory retention in time, or if you look at it from a different perspective, it demonstrates the critical moments when the repetition of the given information should occur.

In theory, it takes about five optimized repetitions to transfer a word into long-term memory. But come on! Learning would be damn easy if this rule would be true for most of the people!

There are a lot of other variables which come into play:

And many others. Still, SRS programs give you the unparalleled upper hand in language learning!

Why use the words which you already know, when you can use dozens of synonyms? You should always try to find gaps in your knowledge.

Of course, using SRS programs like ANKI is not to everyone’s liking. I get it. But let’s look at the list of alternatives, shall we?

Every learner has to face the following problems to learn new words (effectively).

These aren’t some petty, meaningless decisions. These are the decisions that will heavily influence your progress curve.

Here’s an idea that a lot of people have: when you learn a new word, you write it down in a notebook. Then, every few days, you open the notebook and review all the words that you have learned so far.

It works well at first — you no longer forget everything you learn. But very soon it becomes a nightmare.

After you exceed about 1000 words, reviewing your vocabulary starts taking more and more time. And how do you know EXACTLY which words you should review or pay more attention to?

Usually, after no more than a few months, you throw your notebook into the darkest corner of your room and try to swallow the bitter taste of defeat.

It has to be said aloud and with confidence: you will never be as effective as programs in executing algorithms. And choosing when to review a word is nothing more than that – an algorithm.

Many oppose this idea of using SRS programs. And it is indeed mind-boggling why. At least for me. The results speak for themselves.

Currently, I am teaching over 30 people – from students, top-level managers to academics. And one of many regularities I have observed is this: Students of mine who use SRS programs regularly beat students who don’t.

One student of mine, Mathew, quite a recent graduate of Medicine faculty, passed a B2 German exam in just five months. He started from scratch and only knew one language before our cooperation.

At the same time, a Ph.D. from the local university barely moved one level up the language learning ladder. The only difference between them is that Mathew was very consistent with using ANKI (and other strategies).

Really. That’s it.

And it is not that surprising. The technology has been topping the most celebrated human minds for years now. Different AI programs have beaten top players at games like: chess, scrabble and quite recently Go.

Last year, deep learning machines beat humans in the IQ Test. It might seem scary. But only if we treat such a phenomenon as a threat. But why not use the computational powers of a computer to our advantage?

It would be ridiculous to wrestle with Terminator. It’s just as absurd trying to beat computers at optimizing repetitions.

But should everyone use such programs?

I know that you can still be unsure whether or not you should be using SRS programs. That’s why I have decided to create a list of profiles to help you identify your language learning needs:

If you are learning only one language, it’s reasonable to assume that you can surround yourself with it. In this case, using ANKI is not that necessary.

However, things change quite a bit if you are learning your first language, and you have NO previous experience with language learning.

In that case, better save yourself a lot of frustration and download ANKI.

My imagination certainly has its limits since I can’t imagine a representative of any language-related profession that shouldn’t use SRS programs. The risk of letting even one word slip your mind is too high.

Just the material I have covered during my postgraduates studies in legal translation and interpreting amounts to more than 5000 specialized words.

If I wanted to rely on surrounding myself with languages to master them, I would go batshit crazy a long time ago. Who reads legal documents for fun?!

Even if you are not a translator/interpreter yet, but would like to become one in the future, do yourself a favor and download ANKI.

Then I would strongly suggest using ANKI, especially if you would like to become fully fluent in them.

The math is quite easy. Getting to C1 level in 2 languages requires you to know about 20 thousand words. Of course, you should know at least 50-60% of them actively. This number might sound quite abstract, or maybe not that impressive, so let me put it in another way.

Knowing about 10 thousand words in a foreign language is equivalent to having an additional master’s degree. And you know damn well how much time it takes to accumulate this kind of knowledge! It is not time-efficient to acquire this knowledge without trying to optimize your repetitions.

Of course, you can find an exception to every rule. It is not that mentally taxing to imagine a situation where somebody uses one language at work and then another foreign language once they leave the office. Then maybe, just maybe, you can do without SRS programs.

Read more: Here Is Why Most Spaced Repetition Apps Don’t Work For You and How to Fix It.

What do you think about SRS programs? Have you ever used any? Let me know, your opinion is important to me!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 16 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go.

Why even bother with studying pronunciation?

Well, as always, there are no easy answers. Some say it's important to master the pronunciation of a foreign language. Some say it's a waste of time

The question is - why should beginners and semi-advanced learners care?

There are some obvious benefits - the better your pronunciation, the bigger a chance that native speakers will understand you. It means that there is always some minimal amount of work that has to be done in order to talk with native speakers.

Otherwise, each person will soon get discouraged from talking to you and leave or get black-out drunk to match your level of mumbling.

But what comes next after you reach the level, where native speakers have no problems understanding you? Does it make sense to reach for the Holy Grail of learning languages - speaking with no accent?

Considering the amount of time needed, I dare to say no. It's better to spend this time mastering grammar and vocabulary. I have never seen any point in pronouncing everything perfectly while still mixing up words and butchering grammar.

Many people claim to have achieved the level where there is no difference between them and native speakers. I believe that very often this is simply an exaggeration.

Typically, the longer someone talks to a native speaker, the bigger the chance that "the truth gets revealed".

Ultimately, I'll leave that for you to ponder. So what should you do to achieve good pronunciation as quickly as possible?

It won't take long, I promise. If you're interested in practical tips, move to point 1.

To speak clearly, we must first understand what the (highly simplified) building blocks of pronunciation are:

As you can see, mastering pronunciation requires learning the aforementioned elements of a language of your choice.

Now, how to do it practically...

As children, we have the ability to distinguish different sounds and "assemble" them into words (in other words, we combine phonemes into morphemes/words).

The sad part about learning new languages is that we mostly lose this ability when we grow up.

It means, that without preparation very often we won't even know that we pronounce something incorrectly.

That's why the first step to get familiar with pronunciation is to identify the sounds which you might even be not aware of.

How to do it

Every good dictionary has a description of sounds typical of the given language. What's more - as I've written before, always try to choose a dictionary which includes phonetic transcription of words.

" Language x (e.g. Swedish) phonology" will usually deliver best results.

It covers 80+ languages. Choose the one you want and click "alphabet".

Now, after using any of these methods, you'll end up looking confused at the strange set of characters. They are part of the International Phonetic Alphabet. They look scary but are not so difficult to learn.

To become even more aware of the differences between your native and target language, you should learn the sounds of English language.

Here you can find an interactive phonetic chart for English.

Congratulations, by now you should know more or less, what sounds you should pay attention to. To imitate them as precisely as it's only possible, you need (ideally) combination of a couple of methods.

It's a great starting point - grab a dictionary or some textbook and read a description of how you should pronounce given sounds. If the description is accompanied by a picture - even better.

Usually, the biggest problem is how to pronounce vowels. Since your tongue moves up and down, forward or backward, you have plenty of positions to experiment with.

Once (it seems that) you nail the target sound, try to memorize what the position of your tongue and lips was. And don't be too quick thinking that it is over. You have to check it first. (see feedback)

Choose only one or two sounds to begin with. Let's say that you have no idea how to pronounce /æ/.

You check how to produce this sound on Wiki. Then you pick up a word or two and try to pronounce this sound as closely as possible. Say, this word is "tab".

Once you are sure that the sound is pronounced decently, you can move on to other words.

Sounds like a lot of work but I assure you it's not.

When I was a child I suffered from a really bad speech impediment and couldn't pronounce a truckload of sounds in my native tongue.

Can you imagine how I talked to my parents or friends?

- "mc wohn sdno"

- "Yes honey, of course, we love you"

I used this method to learn how to express myself like a normal human being.

Find some interesting text, grab a microphone or use your mobile and start reading aloud using the aforementioned rules.

It won't be difficult - assuming that you did everything right, your mouth will hurt.

It means that you use muscles which haven't been used before.

Of course, If you're learning a language with a different alphabet, you should learn how to read it first.

Now, you can start practicing your hearing. You've successfully identified the sounds which are new to you. It's time you started noticing them in sentences!

Such knowledge gives you immediate head-start when it comes to listening to and communicating with foreigners.

Remember, however, that grammar rules concerning your target language might alter your understanding of speech. Some sounds blend, others are silent or reduced.

For example, in French "à" followed by "le" combine to form "au."

It's always safe to assume that you pronounce sounds at least partially incorrectly until you receive some kind of feedback. Such assumption can save you hours and hours of tears and frustration.

You need final confirmation of how awesome your pronunciation is. And who's better to do it than native speakers?

If you have a tutor or friends who can help you - then great. Ask them all the questions you have and to correct you if there's something wrong.

If you are on your own, try www.rhinospike.com

You can ask native speakers there to record some text for you and then you can use it to compare it with how you speak.

You can also use Google Translate or http://www.forvo.com/ to compare pronunciation of single words. But how will you know that you sound good enough?

You will sound in unison with the recording. Simple as that!

As you can see, learning how to pronounce sounds can be turned into a relatively easy to execute the process. However, as always when it comes to mastering such complex task, the better you try to be, the more time-consuming it is.

And don't beat yourself down, if it doesn't work right away. Good things take time.

A successful man is one who can lay a firm foundation with the bricks others have thrown at him.

If you enjoyed this post, feel free to share it with your friends and join our community!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 10 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.

We've all heard that practice makes perfect. It takes time and effort to be great at something, and if you want to do it right, you should practice one skill at a time.

For example, a beginning guitarist might rehearse scales before chords. A young tennis player practices the forehand before the backhand.

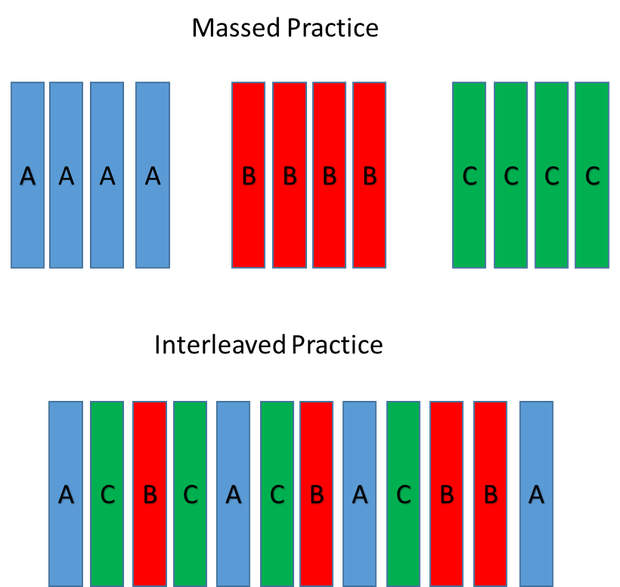

This phenomenon is called “blocking,” and because it appeals to common sense and is easy to schedule, blocking is dominant in schools, training programs, and other settings.

However, the question we should be asking ourselves is this: is blocking the most optimal way to practice skills? It doesn't seem so.

Interestingly, there is a much better strategy - enter "interleaving".

In interleaving one mixes, or interleaves, practice on several related skills together. In other words, instead of going AAAAABBBBBCCCCC you do ABCABCABCABC.

It turns out that varying it even slightly can yield massive gains in a short period.

Let's take baseball as an example: Batters who do batting practice with a mix of fastballs, change-ups, and curveballs hit for a higher average. The interleaving is more effective because when you're out there in the wild, you need first to discern what kind of problem you're facing before you can start to find a solution, like a ball coming from a pitcher's hand.

Read more: A Simple Learning Plan To Get The Most Out Of Your Study Time.

There are almost no strategies that are fully universal and can be used for all disciplines and in all learning conditions. The same goes for interleaved practice.

The past four decades definitely demonstrated that interleaving often outperforms blocking for a variety of subjects, but especially motor learning (e.g., sports). The results for other subjects are mixed.

For example, when native English speakers used the strategy to learn an entirely unfamiliar language (i.e., generating English-to-Swahili translations), the results were better, the same, or worse than after blocking.

Another study (Rohrer et al., 2015) concerning mathematics showed the dramatic benefits of interleaving on children’s performance at math.

During the experiment, some kids were taught math the traditional way. They got familiar with one mathematical technique in a lesson and then practiced it to death. A second group was given assignments that included questions necessitating the use of different techniques.

The results were as impressive as they were surprising.

One day after the test, the students who’d been utilizing the interleaving method did 25% better. However, when tested a month later, the interleaving method did 76% better.

Keep in mind that such an increase is truly amazing, given that both groups had been learning for the same amount of time. The only difference was that some students learned block by block, and others had their learning mixed up.

Read more: How To Master Many Fields Of Knowledge - Your Action Plan And Recommended Strategies.

The results above tell us one important thing. You can't just go cowabunga and start interleaving the heck out of every subject.

Before you do so, you should have some familiarity with subject materials (or the materials should be quickly or easily understood). Otherwise, as appears to be the case for foreign languages, interleaving can sometimes be more confusing than helpful.

It's only logical when you look at this strategy from the memory perspective. For many, using even one technique seems to a burden enough for their working memory. Forcing such people to use three or more make you a psycho who wants to see the world, and their memory, burn.

It's simply too much.

It doesn't take away from the fact that interleaving can be extremely useful. It forces the mind to work harder and to keep searching and reaching for solutions.

However, if you decide to use it, make sure that you're familiar with the strategies you want to interleave. This recommendation is based on a phenomenon called the expertise reversal.

The expertise reversal effect occurs when the instruction that is effective for novice learners is ineffective or even counterproductive for more expert learners.

If you look at it differently, more experienced learners learned more from high variability rather than low variability tasks demonstrating the variability effect. In contrast, less experienced learners learned more from low rather than top variability tasks showing a reverse variability effect.

Why might lower variability be better in the beginning?

It was suggested that more experienced learners had sufficient available working memory capacity to process high variability information. In contrast, less experienced learners were overwhelmed by high variability and learned more using low variability information. Subjective ratings of difficulty supported the assumptions based on cognitive load theory, which you have learned before.

In other words, some signals that are needed by low prior knowledge learners might be redundant for high prior knowledge learners due to their existing schema in long-term memory (Kalyuga, 2009).

For example, one of the experiments (Likourezos, Kalyuga, Sweller, 2019) which tested 103 adults studying pre-university mathematics, showed no interaction between levels of variability (high vs. low) and levels of instructional guidance (worked examples vs. unguided problem solving). The significant main effect of variability indicated a variability effect regardless of levels of instructional guidance.

What does it tell us?

We can't play in the big boy's league if we don't cover the basics!

Read more: The Curse of the Hamster Wheel of Knowledge – Why Becoming a Real Expert Is Very Difficult.

(1) Interleaved practice is perfect for:

(2) For more complicated subjects, make sure to familiarize yourself with the appropriate strategies before you decide to interleave them. This way, you will make sure that your working memory isn't overburdened.

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 11 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.

Nootropics are certainly one of those things that capture your imagination. You pop a pill and everything becomes clear. You are more vigilant, more observant.

Sure, three months down the road you start resembling a patient with a full-blown neurological disorder. You catch yourself scratching your arms nervously while your eyes twitch.

And if your pill is nowhere to be found you drop on the floor and start rhythmically convulsing.

But hey man! Those moments of clarity!

In all seriousness - nootropics have definitely become a thing in the last couple of years. The appeal is understandable.

At the price of a pack of pills, you can become a better version of yourself.

Is it really the case? Nope.

If you ask me, it's definitely more of a fantasy for the naive. Let me explain step-by-step why it is so and what you can do instead to become this sexy learning-machine.

Not everyone is familiar with this notion. Since I don't want to risk keeping you in the dark, let's delve into it.

Nootropics are natural and synthetic compounds that can improve your general cognitive abilities, such as memory, attention, focus, and motivation.

As a rule of thumb, natural nootropics are much safer and can actually improve the brain's health (see Suliman et al. 2016).

As you can see the definition is very far from being precise.

Let's suppose you go into the panic mode before an important meeting and your colleague bitch-slaps you. You suddenly become more focused and sharper.

Can this backhander be treated as a nootropic?

Once again, the definition is unclear. What is clear is that, even though you might not realize it, you probably take some of them already.

Our civilization can pride itself on having a long, rich history of drugging ourselves to feel better and smarter. Here are some of the weapons of the mass enlightening:

If your head bobs like a crazy pigeon if you don't get your daily fix, you are probably not surprised to see it here.

These days, it can be found almost everywhere. Especially in soft drinks, dark chocolate and, of course, in coffee.

Effects:

At normal doses, caffeine has variable effects on learning and memory, but it generally improves reaction time, wakefulness, concentration, and motor coordination. - Nehlig A (2010). "Is caffeine a cognitive enhancer?". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.

L-Theanine, or simply theanine, can generally be found in tea.

The amount is dependent on the kind you drink but generally, you can get more in black tea than in green tea.

Effects:

Increases BDNF and attenuates cortisol-to-DHEAS, also has low affinity for AMPA, kainate, and NMDA receptors.

Great news for any enthusiast of Indian cuisine.

Effect:

Produces neuroprotective effects via activating BDNF/TrkB-dependent MAPK and PI-3K cascades in rodent cortical neurons.

Elevates BDNF by inhibition of GSK-3, which also increases skeletal muscle growth.

One of the most famous herbs which can boast such effects.

Effects:

Improved memory, enhanced focus/attention (similar to caffeine), enhanced mood through reduced anxiety, enhanced performance: reaction time, endurance, memory retention.

I know that you probably want to learn more about "real" nootropics. Here is a short list of some of them.

Effects:

Enhanced brain metabolism, better communication between the right and left brain hemispheres

Effects:

Offers neuroprotection via stimulation of PKC phosphorylation; upregulation of PKCepsilon mRNA; induction of Bcl-X(L), Bcl-w, and BDNF mRNAs; and downregulation of PKCgamma, Bad, and Bax mRNAs.

Effects:

An antioxidant that also stimulates NGF. Found to be a potent enhancer for the regeneration of peripheral nerves.

Effects:

Elevates NGF, BDNF, and GDNF.

Effects:

Stimulates NGF

Effects:

Elevates BDNF by inhibition of GSK-3, which also increases skeletal muscle growth.

Elevation of brain magnesium increased NMDA receptors (NMDARs) signaling, BDNF expression, density of presynaptic puncta, and synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex.

The list goes on and on. As exciting as it all sounds, I would advise against taking most of them. Especially the ones which are intended for the patients with neurological disorders.

If you take caffeine in any form, it might be more than enough for you. Last year, a famous study compared the effectiveness of the CAF+ nootropic to caffeine.

The CAF+ contains a combination of ingredients that have separately shown to boost cognitive performance, including caffeine, l-theanine, vinpocetine, l-tyrosine, and vitamin B6/B12.

It was supposed to be the next big thing in the world of nootropics. Alas, it turned out to be a flop.

Here is the conclusion:

We found that after 90 min, the delayed recall performance on the VLT after caffeine was better than after CAF+ treatment.

Further, caffeine, but not CAF+, improved the performance in a working memory task. In a complex choice reaction task caffeine improved the speed of responding.

Subjective alertness was increased as a result of CAF+ at 30 min after administration. Only caffeine increased diastolic blood pressure.

We conclude that in healthy young students, caffeine improves memory performance and sensorimotor speed, whereas CAF+ does not affect the cognitive performance at the dose tested.

And that's exactly my point. A lot of those compounds which are being plugged shamelessly by different fancy-sounding brain websites are close to useless.

It's not uncommon to find comments on a Reddit about Nootropics saying that:

"500$ for nootropics is not that much. This is just the price of admission for finding the one which is right for you."

It doesn't sound alarming at all. No sir. Don't think of yourself as a cowardly version of a heroin addict. You're a brave brain-explorer! On a more serious note - a lot of these nootropics are not only shady but expensive as well. Keep that in mind, if you decide to try them out.

Even though natural nootropics are potentially safe, or even very safe, it definitely can't be said about synthetic nootropics. By taking them you automatically volunteer to become a guinea pig.

Many of the nootropics change your levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, GABA and many others.

The thing is that so do many drugs like cocaine.

The long-term effect is usually a strong imbalance of transmitter levels in order to compensate those extremes.

It reminds a lot of enthusiasts of brain-zapping couple of years ago. Even though there were almost no double-blind studies confirming its effectiveness, people glibly jumped on this bandwagon.

Of course, you didn't have to wait long for the first papers showing that brain-zapping might not be as great as we once thought.

As Barbara Sahakian and Sharon Morein-Zamir explain in the journal Nature, we don’t know how extended use might change your brain chemistry in the long run.

Call me old-fashioned but if somebody needs a pill every time they want to feel smart or sharp, maybe they are not that smart or sharp? After every use, it's time for a cold and lonely wake-up call.

The important question to ask here is:

what kind of people would like to take such pills in the first place?

There are two groups:

These are people who have probably never put effort into any of the things they have been doing in their life. I know that you're not one of them because you can read. That takes us to the second group.

You know much, you've achieved much but you want more. That's great. That's admirable.

But as a high-achiever, you know that there is no such thing as a lunch for free. Things which are worth your time come with a price.

There are a lot of better, and more permanent, solutions to becoming a person with an extraordinary mind.

Your short-term memory is the bottleneck of your ability to acquire knowledge. By improving it, you can greatly accelerate your learning rate.

Mnemonics are definitely one of the best ways to do it. Read more about improving your short-term memory here.

If you eat like crap (e.g. a lot of processed foods) and you look at a cucumber as if it touched you in your childhood, you should definitely take care of this problem.

If you have problems with brain fog, concentration, and mental sharpness, there is a very good chance that your diet caused a lot of deficiencies. No nootropics will fix that for you.

Get your blood checked to see what minerals and vitamins you're lacking.

Not sure if you lack anything? Check your nails.

Healthy nails should be smooth and have consistent (pinkish) coloring.

Any spots, discoloration and so on should be alarming.

What's more, most of the time, you can basically assume that you lack Vitamin D3. Especially if you have an office job or don't live in a sunny climate. You probably also lack magnesium unless you're a health buff.

More sport and more physical interactions with people. Both these things will give you a nice dopamine and serotonin kick. If you suspect that nobody loves you, try hugging stray dogs. Even this will do.

Call me biased but no pill will substitute this kind of knowledge. Let's assume that you want to learn a language and you gobbled up a magical tablet. If you use bad learning strategies, you will still get nowhere. This time, however, a little bit faster than before.

Knowing how to learn is a permanent power.

If you don't know how to prioritize, nootropics will only make you browse all the cat pictures faster. Here is a good place to start.

Doing something all the time is definitely one of the worst learning strategies ever. Breaks and a good night sleep are a part of the job.

I should know. I consistently ignore and rediscover this piece of advice.

There are dozens of mental models and biases which invisibly shape the decisions you make. Get to know them in order to reason more efficiently.

This is probably the best piece of advice I can offer anyone. You need a lot of facts in order to think efficiently and recognize patterns.

Their accumulation won't happen overnight. It can be most aptly explained by one of my all-time favorite anecdotes.

Knowledge builds on knowledge; one is not learning independent bits of trivia.

Richard Hamming recalls in You and Your Research:

You observe that most great scientists have tremendous drive. I worked for ten years with John Tukey at Bell Labs. He had tremendous drive.

One day about three or four years after I joined, I discovered that John Tukey was slightly younger than I was. John was a genius and I clearly was not.

Well, I went storming into Bode’s office and said, How can anybody my age know as much as John Tukey does?

He leaned back in his chair, put his hands behind his head, grinned slightly, and said,

You would be surprised Hamming, how much you would know if you worked as hard as he did that many years. I simply slunk out of the office!

What Bode was saying was this: Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest.

Given two people of approximately the same ability and one person who works 10% more than the other, the latter will more than twice outproduce the former.

The more you know, the more you learn; the more you learn, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more the opportunity - it is very much like compound interest.

I don’t want to give you a rate, but it is a very high rate.

Given two people with exactly the same ability, the one person who manages day in and day out to get in one more hour of thinking will be tremendously more productive over a lifetime.

I took Bode’s remark to heart; I spent a good deal more of my time for some years trying to work a bit harder and I found, in fact, I could get more work done.

As enticing as nootropics might seem, I would strongly advise against using them. There are literally dozens of other, more permanent solutions, which you should try out first.

And I can tell you this - once you try most of them, you won't even remember why you wanted to give them a try in the first place.

Would you ever consider trying nootropics? Let me know in the comments!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 26 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.

Not everyone is equal in the kingdom of languages. There is one group that is mercilessly oppressed — one group which suffers from a crippling disease called SOCIAL ANXIETY.

It’s a terrible, terrible malady. It doesn’t matter how hard you try to keep your fears and anxiety in a padded cell of your brain. They always scrape their way out to feed your soul with poison. Even if only through the cracks.

But does it mean that you can’t learn a language because of it? Hell no!

I used to suffer from anxiety-induced panic attacks in the past. I sat in my room for days with curtains closed until I ran out of food. Those days are, luckily, long gone. Although anxiety still looms the dark corners of my mind.

So if you are also a victim of this condition – don’t worry. Here is the list of six ideas that you can use to learn to speak a foreign language with social anxiety.

There is a good chance that you don’t want to talk to others because you don’t know them.

You don’t feel comfortable baring your soul in front of them. Every cell in your brain sends you warning signals – watch out; they are out to get you.

But you don’t feel this way around friends or people you trust, do you?

That’s why this is probably the best way to approach language learning for those anxiety stricken. You won’t be able to get any panic attacks or feel anxious with a friend by your side.

Discussing anything becomes much easier when you grow attached to another person. You don’t even have to suffer from anxiety to be able to benefit from such a relationship.

Having such contact with another person drastically changes the way you experience lessons.

You don’t sit in front of a stranger who doesn’t give a shit about your day or well-being. You sit in front of someone who cares. Such a bond makes all the conversations much more meaningful and memorable, as well.

That’s why you should pay close attention to a person who will become your language partner or your teacher.

Look for similarities. Try a lesson to make sure that this person is trustworthy. And, what’s most important, don’t be a weirdo. “Hi, my name is Bartosz. Do you wanna be my friend?”. Ugh.

What 99% of people seem to miss is that you don’t necessarily need countless hours of talking with others to be able to communicate freely in your target language.

Why?

Because almost all hard work is done in solitude.

Learning vocabulary, grammar, listening. All that you can do on your own.

Of course, it’s great to have some private lessons from time to time to make sure that you are on the right track. But other than that – you will be fine on your own. You can create your feedback loops to make sure that you are speaking correctly.

But how can you practice speaking on your own?

Don’t know a word? Write it down. Do you know a word? Try to find a synonym! Depending on your preferences, you might look it up immediately or save it for later.

You can even scribble these questions on a piece of paper and write down needed vocabulary on the flip side. It will allow you to answer the same question again in the following days.

EXAMPLE:

Q: Why do you hate Kate? (translated into your target language)

A: (needed vocabulary) brainless chatterbox, pretentious

As you can see, you don’t need to be serious when you answer these questions.

Heck, the questions themselves don’t need to be serious!

Have fun!

Q: Have you ever tried eating with your feet?

Q: If you were a hot dog, what kind of hot dog would you be?

The greatest thing of all about learning to talk like this is that nobody judges you. You might mispronounce words in your first try. You might forget them.

And guess what? Nothing. Nothing will happen.

Once you get good and confident enough, you can start talking with others.

I find it quite often to be more effective than real conversations. I know, I know. On the surface, it might seem absurd. There is no interaction, after all.

However, if you look beyond the superficial, you will be able to see that self-talk offers you a lot of opportunities that real-life conversations can’t.

For example, self-talk gives you a chance to activate less frequent words.

I can talk for 20 minutes with myself about cervical cancer. Could I do it with someone else? Let’s try to imagine such a conversation.

– “Hi, Tom! Wanna talk about cervical cancer? It will be fun! I promise!”

– “Stay away, you weirdo!’

– “Cool! Some other time then.”

Read more: Benefits Of Talking To Yourself And How To Do It Right To Master a Language.

Talking doesn’t necessarily mean discussing philosophical treatises face-to-face. It’s perfectly fine to stick to written communication. In the era of the internet, you are just a few clicks away from millions of potential language partners.

Here is a list of websites where you can find some language exchange partners:

Don’t want to talk to others? Don’t worry. You still might activate your vocabulary. Start writing daily. Anything really will do. It can be a diary, a blog, some observations.

Make it difficult for yourself and choose some difficult subject to jog your mind. It can even be some erotic novel! “The secret erotic life of ferns,” for example. Yep. I like this one.

Read more: Writing or speaking – what is better memory-wise for learning languages?

We might be the pinnacle of evolution, but in some regards, we are no different from your average gopher or a sloth. You can easily get conditioned to react to specific circumstances in a given way.

Why? Habituation. That’s why.

Habituation is a form of learning in which an organism decreases or ceases to respond to a stimulus after repeated presentations. Essentially, the organism learns to stop responding to a stimulus which is no longer biologically relevant. For example, organisms may habituate to repeated sudden loud noises when they learn these have no consequences.

Habituation usually refers to a reduction in innate behaviours, rather than behaviours developed during conditioning in which the process is termed “extinction”. A progressive decline of a behavior in a habituation procedure may also reflect nonspecific effects such as fatigue, which must be ruled out when the interest is in habituation as a learning process. – Wikipedia

Once you learn that all that gloom and doom is only in your head, you can start modifying your behavior (you can read more about it in Dropping Ashes on the Buddha: The Teaching of Zen Master Seung Sahn. Highly recommended!)

You can leverage this rule and condition yourself to become a braver version of yourself. Maybe you won’t get I-will-slay-you-and-take-your-women brave in two weeks, but it will get you started.

Your action plan is simple but not easy.

Find situations where you can expose yourself to stressors

As Oscar Wilde used to say, “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” And only you know how deep you are stuck in this anxiety gutter.

Choose your first task accordingly, and move your way up from there. Don’t make it too easy or too hard on yourself.

Some of the things you might do are:

In other words, just leave a comment somewhere. You don’t even have to go back to check responses!

Any start is a good start as long as you start.

There is a good chance that you have heard about reframing your thoughts. The basic premise is very simple.

Every time you catch yourself being anxious about some situation, you should look at it from a different perspective.

Instead of saying, “Gosh, she sure wouldn’t like to talk with me,” you can change it to, “I bet she is bored right now and would love to have a nice chat with me.”

I know. It sounds corny.

The first time I heard this piece of advice, I felt as if a ragged hobo tried to jam a lump of guano in my hand, saying, “Just pat it into your face, and you will gain superpowers.”

Little did I know that this advice is as brilliant as it is simple. Much water passed under the bridge before I finally started applying it.

But why does it work? Because such is the nature of memories. They are not set in stone and perennial.

Research conducted by Daniela Schiller, of Mt. Sinai School of Medicine and her former colleagues from New York University, shows us something truly amazing.

Schiller says that “memories are malleable constructs that are reconstructed with each recall. We all recognize that our memories are like Swiss cheese; what we now know is that they are more like processed cheese.

What we remember changes each time we recall the event. The slightly changed memory is now embedded as “real,” only to be reconstructed with the next recall. – Source

So what does it all mean?

It means that adding new information to your memories or recalling them in a slightly different context might alter them.

How much? Enough for you to recalibrate how you perceive the world around you! It’s up to you how much you want to reshape your perception of reality.

It seems like a strange statement. But the truth is that not everyone needs to learn how to speak a language.

Before you dive into the language learning process, be sure that it’s something you want. You shouldn’t feel pressured into doing so just because others do. You don’t want to spend hundreds of extra hours on something you are not going to use.

Remember that every language, even the tiniest of them all, is a skeleton key to the vastness of materials – books, movies, anecdotes, etc. It’s fine to learn a language to be able to access them all.

Here is a quick summary of all the strategies mentioned above.

Overcoming your language learning anxiety can be hard, but it is certainly doable. When in doubt, always keep in mind that our reality is negotiable to a large degree – if you believe you can change, it is possible.

What’s more, you shouldn’t forget that the real work is always done in solitude. Teachers or language partners might show you what to concentrate on, but it’s up to you to put this knowledge into practice.

You don’t have to limit yourself to activating your vocabulary only through speaking. Writing is also a very desirable option.

Lastly, remember that changing your diet can also be very helpful. You can do it, for example, by introducing anti-inflammatory foods like turmeric.

Back to you.

Can you share any tricks/methods which helped you overcome your language learning anxiety?

No advice is too small or trivial. As always, feel free to comment or drop me a message.

There are just a few things in this world which make me angry and sad at the same time.

But the one that takes the cake is reading almost every month for the past few years that soon, oh so very soon, learning languages will become obsolete.

Sure, it is pointless. Why bother? Technology will solve the problem of interlingual communication. So better not waste your time. You’ll be better-off watching re-runs of The Kardashians.

How many people have given up even before they started? Without even realizing that many, oh so many, years will pass before any translation software or magical devices will be able to do a half-decent job.

But is it really only about communication? Have you ever wondered what other benefits language learning has to offer?

The following list includes 80 benefits of language learning. Some obvious, some surprising.

I’ve been hand-picking them for many months from different scientific sources.

The list is a work in progress. I’ll keep on updating it every couple of months.

Feel free to write to me if you spot somewhere some benefit which is not on the list.

It’s also worth noting that there is a large body of research to confirm each of these benefits of language learning.

Although, I usually quote results of just one or two studies to keep this list more concise.

Purpose of the list

The main purpose of this list is to make you realize how many benefits of language learning there are.

I hope that such knowledge will help to pull you through all language-learning plateaus.

What’s more, I also hope that it will help you to inspire others to pursue language learning.

Your children, spouse, parents. It’s never too late.

Treat is a language-learning manifesto. Print it, hang it on the wall. And every time you feel like giving up, hug your dictionary and stare at this list for a couple of minutes.

If you learn a foreign language…

Johan Martensson’s research shows that after three months of studying a foreign language, learners’ brains grew in four places: the hippocampus, middle frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus (gyri are ridges on the cerebral cortex).

What happens when you learn languages for more than 3 months and you’re serious about it?

The right hippocampus and the left superior temporal gyrus were structurally more malleable in interpreters acquiring higher proficiency in the foreign language. Interpreters struggling relatively more to master the language displayed larger gray matter increases in the middle frontal gyrus

References:

(Johan Mårtensson, Johan Eriksson, Nils Christian Bodammerc, Magnus Lindgren, Mikael Johansson, Lars Nyberg, Martin Lövdén (2012). “Growth of language-related brain areas after foreign language learning“.)

According to research conducted by Julia Morales of Spain’s Granada University, children who learn a second language are able to recall memories better than monolinguals, or speakers of just one language.

When asked to complete memory-based tasks, Morales and her team found that those who had knowledge of multiple languages worked both faster and more accurately.

The young participants who spoke a second language had a clear advantage in working memory. Their brains worked faster, pulling information and identifying problems in a more logical fashion.

When your brain is put through its paces and forced to recall specific words in multiple languages, it develops strength in the areas responsible for storing and retrieving information (read more about improving your short-term memory)

References:

(Julia Morales, Alejandra Calvo, Ellen Bialystok (2013). “Working memory development in monolingual and bilingual children“.)

Do you remember how hard listening was at the beginning of the language journey? Pure nightmare!

And since the brain has to work really hard to distinguish between different types of sounds in different languages, being bilingual leads to improved listening skills (Krizman et al., 2012).

Further references:

Lapkin, et al 1990, Ratte 1968.

In 1962, Peal and Lambert published a study where they found that people who are at least conversationally fluent in more than one language consistently beat monolinguals on tests of verbal and nonverbal intelligence.

Bilinguals showed significant advantage especially in non-verbal tests that required more mental flexibility.

References:

Peal E., Lambert M. (1962). “The relation of bilingualism to intelligence”.Psychological Monographs75(546): 1–23.

Photo by Lex Mckee

A study from 2010 shows that bilinguals have stronger control over their attention and are more capable of limiting distractions.

When asked to concentrate on a task, the study’s bilingual participants showed an increased ability to tune out distractions and concentrate on the given task.

They were also better equipped to interpret the work before them, eliminating unnecessary information and working on only what was essential.

References:

Ellen Bialystok, Fergus I. M. Craik (2010). “Cognitive and Linguistic Processing in the Bilingual Mind“.

Great news everyone! The recent evidence suggests a positive impact of bilingualism on cognition.

So what exactly does it mean?

The research found that individuals who speak two or more languages, regardless of their education level, gender or occupation, experience the onset of Alzheimer’s, on average, 4 1/2 years later than monolingual subjects did.

What’s more, even people who acquired a second language in adulthood can enjoy this benefit!

References:

Thomas H. Bak, Jack J. Nissan, Michael M. Allerhand, Ian J. Deary (2014). “Does bilingualism influence cognitive aging?“.

I’m not a fan of multitasking since it’s harmful to your productivity.

However, according to research conducted by Brian Gold, learning a language increases brain flexibility, making it easy to switch tasks in just seconds. Study participants were better at adapting and were able to handle unexpected situations much better than monolinguals.

That’s great. But the real question is – why were they better?

The plausible explanation is that when we learn a new language, we frequently jump between our familiar first language and the new one, making connections to help us retain what we’re learning.

This linguistic workout activates different areas of our brain. The more we switch between languages, the more those brain zones become accustomed to working. Once they’ve become accustomed to this type of “workout,” those same areas start helping to switch between tasks beyond language.

References:

Brian T. Gold, Chobok Kim, Nathan F. Johnson, Richard J. Kryscio and Charles D. Smith (2013). “Lifelong Bilingualism Maintains Neural Efficiency for Cognitive Control in Aging“.

Learning a foreign language improves not only your ability to solve problems and to think more logically. It can also increase your creativity, according to Kathryn Bamford and Donald Mizokawa’s research.

Early language study forces you to reach for alternate words when you can’t quite remember the original one you wanted to use and makes you experiment with new words and phrases.

It improves your skills in divergent thinking, which is the ability to identify multiple solutions to a single problem.

Language learners also show greater cognitive flexibility (Hakuta 1986) and are better at figural creativity (Landry 1973).

References:

Kathryn W. Bamford, Donald T. Mizokawa (2006). “Additive-Bilingual (Immersion) Education: Cognitive and Language Development“.

It sounds impressive, doesn’t it? But before we move on, let’s clarify what executive functions are:

Executive functions (also known as cognitive control and supervisory attentional system) – is an umbrella term for the management (regulation, control) of cognitive processes, including working memory, reasoning, task flexibility, and problem solving as well as planning and execution. – Wikipedia

The body of research has shown that bilingual individuals are better at such processes; suggesting an interaction between being bilingual and executive functions.

As Anne-Catherine Nicolay and Martine Poncelet, a pair of scientists from Belgium, discovered in their research, learning a language improves individuals’ alertness, auditory attention, divided attention, and mental flexibility. The more you immerse yourself in the new language, the more you hone your executive functions.

In another study, Bialystok gave study subjects a non-linguistic card-sorting task that required flexibility in problem-solving, filtering irrelevant information, as well as recognizing the constancy of some variables in the face of changes in the rules.

Bilingual children significantly outperformed their monolingual peers in this task, suggesting the early development of inhibitory function that aids in solving problems that require the ability to selectively focus attention.

References:

– Bialystok E. (1999). “Cognitive complexity and attentional control in the bilingual mind“. Child Development 70 (3): 636–644)

– Anne-Catherine Nicolay, Martine Poncelet (2012). “Cognitive advantage in children enrolled in a second-language immersion elementary school program for three years“.

In one study, bilingual children were presented with the problems of both mathematical (arranging two sets of bottle caps to be equal according to instruction) and non-mathematical nature (a common household problem represented in pictures) and were asked to provide solutions.

They were rated on scales of creativity, flexibility, and originality. The results confirmed that the bilingual children were more creative in their problem solving than their monolingual peers.

One explanation for this could be bilinguals’ increased metalinguistic awareness, which creates a form of thinking that is more open and objective, resulting in increased awareness and flexibility.

References:

Mark Leikin (2012). “The effect of bilingualism on creativity: Developmental and educational perspectives“.

If you want to create a crazy brainiac, teaching your child another language is a way to go!

According to new research, babies exposed to two languages display better learning and memory skills compared to their monolingual peers.

The study was conducted in Singapore and was the result of the collaboration between scientists and hospitals. Altogether, the study included 114 6 month-old infants – about half of whom had been exposed to two languages from birth.

The study found that when repeatedly shown the same image, bilingual babies recognized familiar images quicker and paid more attention to novel images – demonstrating tendencies that have strong links to higher IQ later in life.

“The power to learn a language is so great in the young child that it doesn’t seem to matter how many languages you seem to throw their way…They can learn as many spoken languages as you can allow them to hear systematically and regularly at the same time. Children just have this capacity. Their brain is ripe to do this…there doesn’t seem to be any detriment to….develop[ing] several languages at the same time” according to Dr. Susan Curtiss, UCLA Linguistics professor.

Past studies have shown that babies who rapidly get bored with a familiar image demonstrated higher cognition and language ability later on as children (Bialystok & Hakuta 1994; Fuchsen 1989).

A preference for novelty is also linked with higher IQs and better scores in vocabulary tests during pre-school and school-going years.

Leher Singh, Charlene S. L. Fu, Aishah A. Rahman, Waseem B. Hameed, Shamini Sanmugam, Pratibha Agarwal, Binyan Jiang, Yap Seng Chong, Michael J. Meaney, Anne Rifkin-Graboi (2014). “Back to Basics: A Bilingual Advantage in Infant Visual Habituation“.

You can never understand one language until you understand at least two.

How many monolingual speakers know what adjectives or gerunds are? Not many. It’s natural. They simply don’t need such knowledge. However, learning a second language draws your attention to the abstract rules and structure of language, thus makes you better at your first language.

Research suggests that foreign language study “enhances children’s understanding of how language itself works and their ability to manipulate language in the service of thinking and problem-solving.” (Cummins 1981).

Read more about improving your listening skills here.

The research shows a high positive correlation between foreign language study and improved reading

scores for children of average and below-average intelligence. (Garfinkel & Tabor 1991).

Read more about reading more efficiently here.

It sounds like a cliche but let’s say it out loud – your chances of employment in today’s economy are much greater for you than for those who speak only one language.

Multilingual employees are able to communicate and interact within multiple communities. With the rise of technology which enables global communication, such an ability becomes more and more valuable.

What’s more, knowledge of a foreign language conveys, among others, that you’re an intelligent, disciplined and motivated person.

Even if being bilingual is not completely necessary in your field, being fluent in another language gives you a competitive edge over your monolingual competitors.

In a survey of 581 alumni of The American Graduate School of International Management in Glendale, Arizona, most graduated stated that they had gained a competitive advantage from their knowledge of foreign languages and other cultures.

They said that not only was language study often a decisive factor in hiring decisions and in enhancing their career paths, but it also provided personal fulfillment, mental discipline, and cultural enlightenment. (Grosse 2004)

Confidence always increases when a new skill is mastered. Learning a foreign language is no different.

It boosts your self-confidence and makes you feel this nice, warm feeling inside.

Knowing a language also makes you more interesting and let’s face it – who doesn’t want to be more interesting?

Evidence from several studies shows language students to have a significantly higher self-concept than do non-language students. (Masciantonio 1977, Saunders 1998, Andrade, et al. 1989).

Photo by Dennis Skley

Bilingual students consistently score higher on standardized tests in comparison with their monolingual peers, especially in the areas of math, reading and vocabulary.

How much better are their results?

Results from the SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test ) show that students who completed at least four years of foreign-language study scored more than 100 points higher on each section of the SAT than monolingual students. (College Board 2004)

Even third-graders who had received 15 minutes of conversational French lessons daily for a year had statistically higher SAT scores than their peers who had not received French classes. (Lopata 1963)

In a small study, bilingual people were about a half-second faster than monolinguals (3.5 versus 4 seconds) at executing novel instructions such as “add 1 to x, divide y by 2, and sum the results.”

Andrea Stocco and Chantel S. Prat of the University of Washington who conducted the research say the findings are in line with previous studies showing that bilingual children show superior performance on non-linguistic tasks.

References:

Stocco, A., Yamasaki, B. L., Natalenko, R., & Prat, C. S. “Bilingual brain training: A neurobiological framework of how bilingual experience improves executive function.” International Journal of Bilingualism.

Mastering a language is a skill that requires a lot of time, discipline and persistence.

Many people start learning and give up half-way.

That’s why employees who have knowledge of a foreign language are much harder to replace.

Of course, the rarer and /or more difficult the language, the stronger your leverage.

It comes as no surprise that the knowledge of languages can add a little something to your salary.

However, the amount you can get varies significantly from country to country.

So how does it look like for the citizens of the United States?

Albert Saiz, the MIT economist who calculated the 2% premium, found quite different premiums for different languages: just 1.5% for Spanish, 2.3% for French and 3.8% for German. This translates into big differences in the language account: your Spanish is worth $51,000, but French, $77,000, and German, $128,000. Humans are famously bad at weighting the future against the present, but if you dangled even a post-dated $128,000 cheque in front of the average 14-year-old, Goethe and Schiller would be hotter than Facebook. – (www.economist.com)

In the UK, employees who know a foreign language earn an extra £3,000 a year – a total of £145,000 over their lifetime

Companies are prepared to pay workers earning the national average of £25,818 as much as 12% more if they speak or learn a foreign language. For higher earners, the figures are even more startling.

Those earning £45,000 could see a potential cash boost of 20%, amounting to an extra £9,000 a year or £423,000 over a lifetime. – (www.kwintessential.co.uk)