Pictures and Images in Flashcards – Are They Even Useful?

Have you noticed a trend that has been going on for quite many years now? Almost every app out there seems to be using pictures. It's been touted as a magical cure for your inability to learn.

But is it really the case or maybe it's another thinly veiled attempt to talk you into buying a premium version of some crappy app?

Unfortunately, it seems to be the latter. Yes, learning with pictures has its benefits, but they are relatively tiny compared to the effort and other potential strategies you might use.

Let's investigate step by step why it's so!

Potential benefits of learning with pictures

One picture is worth 1000 words, as the saying goes, and I am pretty sure that every child who ever wandered into their parent's bedroom in the middle of the night can attest to this. But what's important to you, as a learner, is how many benefits can learning with pictures offer you. After all, you wouldn't want to waste too much time adding them to your flashcards if they are useless.

The Picture Superiority Effect (i.e. you remember pictures better)

If we want to discuss advantages of using pictures, we much touch upon the picture superiority effect. This is a go-to argument of many proponents of this approach to learning.

The picture superiority effect refers to the phenomenon in which pictures and images are more likely to be remembered than words.

It's not anything debatable- the effect has been reproduced in a variety of experiments using different methodologies. However, the thing that many experts seem to miss is the following excerpt:

pictures and images are more likely to be remembered than words.

It just means we are great at recognizing pictures and images. It has its advantages but it's not should be confused with being able to effortlessly memorize vocabulary.

Let's quickly go through some studies to show you how amazingly well we can recognize pictures.

Power of recognition memory (i.e. you're good at recognizing pictures)

In one of the most widely-cited studies on recognition memory. Standing showed participants an epic 10,000 photographs over the course of 5 days, with 5 seconds’ exposure per image. He then tested their familiarity, essentially as described above.

The participants showed an 83% success rate, suggesting that they had become familiar with about 6,600 images during their ordeal. Other volunteers, trained on a smaller collection of 1,000 images selected for vividness, had a 94% success rate.

But even greater feats have been reported in earlier times. Peter of Ravenna and Francesco Panigarola, Italian memory teachers from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, respectively, were each said to have retained over 100,000 images for use in recalling enormous amounts of information. - Robert Madigan - How Memory Works and How To Make it Work For You

Now that we have established that we're pretty good at recognizing images, let's try to see if pairing words with pictures offers more benefits.

Boosting your recall

Another amazing benefit of using pictures as a part of your learning strategy is improving your recall. This process occurs in the following way:

During memory recall, neurons in the hippocampus began to fire strongly. This was also the case during a control condition in which participants only had to remember scene images without the objects. Importantly, however, hippocampal ativity lasted much longer when participants also had to remember the associated object (the raspberry or scorpion image). Additionally, neurons in the entorhinal cortex began to fire in parallel to the hippocampus.

The pattern of activation in the entorhinal cortex during successful recall strongly resembled the pattern of activation during the initial learning of the objects," explains Dr. Bernhard Staresina from the University of Birmingham." - The brain's auto-complete function, New insights into associative memory

It's worth pointing out that even the evidence for improved recall is limited and usually concerns abstract words and idiomatic expressions.

Farley et al. (2012) examined if the meaning recall of words improved in the presence of imagery, and found that only the meaning recall of abstract words improved, while that of concrete nouns did not. A possible interpretation of this finding is that, in the case of concrete nouns, most learners can naturally produce visual images in their mind and use them to remember the words.

Therefore, the Vocabulary Learning and Instruction, 6 (1), 21–31. 26 Ishii:

The Impact of Semantic Clustering additional visual images in the learning material do not affect the learning outcome, since they are already present in their mind. However, in the case of abstract nouns, since it is often difficult for learners to create images independently, the presentation of imagery helps them retain the meaning of the words they are trying to learn.

Jennifer Aniston neurons

It seems that this improved recall is caused by creating immediate associations between words and pictures when they are presented together.

The scientists showed patients images of a person in a context e.g. Jennifer Aniston at the Eiffel Tower, Clint Eastwood in front of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, Halle Berry at the Sidney Opera House or Tiger Woods at the White House. They found that the neuron that formerly fired for a single image e.g. Jennifer Aniston or Halle Berry, now also fired for the associated image too i.e. the Eiffel Tower or Sidney Opera House.

"The remarkable result was that the neurons changed their firing properties at the exact moment the subjects formed the new memories – the neuron initially firing to Jennifer Aniston started firing to the Eiffel Tower at the time the subject started remembering this association,” said Rodrigo Quian Quiroga, head of the Centre for Systems Neuroscience at the University of Leicester." - Researchers Make a “Spectacular Discovery” About Memory Formation and Learning

To sum it up, we know that:

Let me make it clear - these benefits are undeniable, and they have their use in the learning process. However, the real question is - how effective are pictures at helping you memorize and recall vocabulary!

How effective are pictures at helping you memorize and recall vocabulary

Before I move on to the science, let's start with my personal experiments. Contrary to a lot of "language experts" online, I rarely believe anything I read unless I see lots of quality scientific support for some specific claims. And believe me, it's not easy. Most of scientific studies are flawed on so many different levels that they shouldn't be written at all.

Once I have gathered enough evidence, I start running long-term statistical experiments in order to see what benefits a given approach brings to the table.

Read more about experimenting: Fail Fast and Fail Epicly – The Best Way Of Learning Languages

What's the answer in that case? Not that much. Most of the time you will be able to just remember a picture very well. Possibly, if the picture represents accurately a meaning of a given word, you might find it easier to recall the said meaning. Based on my experiments I can say that the overall benefit of using pictures in learning is not big and amounts to less than 5-10%.

Effect of pairing words and pictures on memory

Boers, Lindstromberg, Littlemore, Stengers, and Eyckmans (2008) and Boers, Piquer Píriz, Stengers, and Eyckmans (2009) investigated the effect of pictorial elucidation when learning new idiomatic expressions.

The studies revealed that learners retain the meanings of newly learned idiomatic items better when they are presented with visual images. Though there was no impact for the word forms, such presentations at least improved the learning of word meanings.

In other words, using pictures can improve your understanding of what a word, or an idiom, means.

One of the problems I have with most memory-related studies is that scientists blatantly ignore the fact that familiarity with words might heavily skew the final results. For that reason, I really love the following paper from 2017.

Participants (36 English-speaking adults) learned 27 pseudowords, which were paired with 27 unfamiliar pictures. They were given cued recall practice for 9 of the words, reproduction practice for another set of 9 words, and the remaining 9 words were restudied. Participants were tested on their recognition (3-alternative forced choice) and recall (saying the pseudoword in response to a picture) of these items immediately after training, and a week after training. Our hypotheses were that reproduction and restudy practice would lead to better learning immediately after training, but that cued recall practice would lead to better retention in the long term.

In all three conditions, recognition performance was extremely high immediately after training, and a week following training, indicating that participants had acquired associations between the novel pictures and novel words. In addition, recognition and cued recall performance was better immediately after training relative to a week later, confirming that participants forgot some words over time. However, results in the cued recall task did not support our hypotheses. Immediately after training, participants showed an advantage for cued Recall over the Restudy condition, but not over the Reproduce condition. Furthermore, there was no boost for the cued Recall condition over time relative to the other two conditions. Results from a Bayesian analysis also supported this null finding. Nonetheless, we found a clear effect of word length, with shorter words being better learned than longer words, indicating that our method was sufficiently sensitive to detect an impact of condition on learning. - The effect of recall, reproduction, and restudy on word learning: a pre-registered study

As you can see, conclusions are not that optimistic and almost fully coincide with my own experiments. That's why I would suggest you don't add pictures to every flashcard. It's too time-consuming compared to benefits. However, if you really enjoy learning this way, I will suggest to you in a second a better way to utilize pictures.

Test it for yourself!

I know that the above could be a bit of a buzz-kill for any die-hard fan of all those flashy flashcard apps and what not. But the thing is, you should never just trust someone's opinion without verifying it.

Run your own experiment. See how well you retain those pictures and if it really makes a difference result-wise compared to the invested time. Our time on this pancake earth is limited. No need to waste any of it using ineffective learning methods.

It doesn't take much time and it will be worth more than anyone's opinion. If you decide to go for it, make sure to run it for at least 2-3 months to truly verify of pictures offer a long-term memory boost.

How to use picture more effectively in your learning

Since my initial results with this method weren’t very satisfying I decided to step it up and tried to check how different kind of pictures affect my recall. What’s more, I also verified how using the same picture in many flashcards affects my learning.

What kind of pictures did I use?

I concentrated on pictures which are emotionally salient. I tried everything starting from gore pictures to porn pictures. The results, especially with the latter, weren’t very good. I was sitting there like a horny idiot and couldn’t concentrate even one bit on any of the words. It’s like having a sexy teacher in high school. You can’t wait till you get to your classes but once you do, you don’t hear any words.

Funny enough, I remember most of the pictures, but now words, from this experiment to this day which only further proves to me that your typical approach won’t work here.

So what kind of pictures did work?

Pictures from my personal collection. I found out that if I use one picture in a lot of flashcards where every flashcard concentrates on one word, I am able to recall words extremely easily. In addition, my retention rate has also been improved, although not as significantly as my ability to retrieve words.

The main takeaway (i.e. what I learned):

If you want to use pictures in your language studies, don’t waste time trying to find a new picture for every word. Choose one picture and use it multiple times in different flashcards. Each time try to memorize a different word.

What's more, if it's only possible, try to stick to pics from your personal collection - a weekend at your grandma's, uncle Jim getting sloshed at your wedding. You know, good stuff!

Summary

Pictures are a definitely a nice addition to your learning toolkit. However, in order to be able to use them effectively you need to understand that they won't help you much with memorizing words. The best thing they can offer is a slight boost in remembering words and significantly improved recall for pictures. That's why don't waste your time trying to paste a picture into every flashcard. Benefits will be minuscule compared to your effort.

If you really want to get the biggest bang for your buck learning-wise, try to use one picture to memorize many words. That's a great way of mimicking the way we originally started acquiring vocabulary. And it's not very time-consuming.

Once you try this method, let me know how it worked for you!

What are your thoughts on using pictures in flashcards? Let me know in the comments!

Done reading? Time to learn!

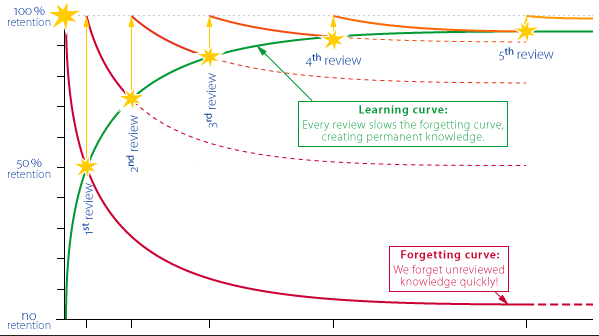

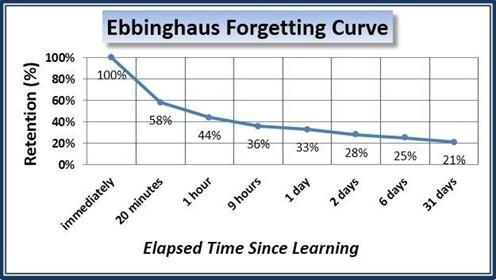

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 9 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.