The Goldlist Method – A Scientific Critique And Why It’s a Waste of Time

Choosing the right learning methods has always been one of the most daunting tasks for most language learners. No wonder. Around every corner, you can find yet another popular learning strategy.

But how do you know it’s effective? Is it actually based on any real science?

Most people can offer you just their opinions. I am here to show you step-by-step what are the biggest flaws of various language learning methods. In other words, I am going to scrutinize them and show you what their authors don’t know or don’t want to reveal.

The first position on the menu today is the Goldlist method.

Before I start, it’s worth mentioning that this article is not meant to offend the author of the Goldlist method nor disparage anyone who is using it but to show one simple fact – it’s extremely easy to come up with a method but it doesn’t mean it’s effective memory-wise.

The Goldlist Method – What Is It All About?

Unless you are into experimenting with various learning methods, you may not have heard of the Goldlist Method. For that reason, I will try to outline what’s all about so we are on the same page.

First of all, here is a great video that sums up what this method is all about.

If you are old-fashioned, here is a description of how it works.

- Get a large (A4 size) notebook. This is going to be your “bronze” book.

- Prepare the materials (i.e. words) you’re interested in. The items you choose will go into your “head list”.

- Open your book and write the first twenty-five words or phrases down, one below the other, on the left-hand side of the individual page. Include any integral information such as gender or plural forms of nouns or irregular aspects of a verb’s conjugation. The list shouldn’t take you more than twenty minutes to do.

- When the list is ready, read through it out loud, mindfully but without straining to remember.

- When you start the next piece of the head list, number it 26-50, then 51-75 and so on.

- The first distillation – after at least two weeks open your notebook and cast your eye towards your first list of 1 to 25 (or, 26 to 50, or 9,975 to 10,000) depending on which double spread you’re at. The “two weeks plus” pause is important. It’s intended to allow any short-term memories of the information to fade completely so that you can be sure that things you think you’ve got into the long-term memory really are in there. Make sure, then, that you date each set of twenty-five head list items (something I haven’t done in my illustrative photos for this article).

David James says that there is no upper limit to the gap between reviews, though suggests a maximum of two months, simply to keep up momentum.

- Discard eight items, and carry the remaining seventeen into a new list, This will be your first “distillation”.

- Repeat the process for the second and third distillations (the third and fourth list on your double spread). The interval should be at least 2 weeks.

- For the fourth distillation, you start a new book, your “silver” book.

- The “gold” notebook works the same way, the hardcore items from the “silver” notebook’s seventh distillation are carried over to the “gold” for new head list of twenty-five lines (distillation number eight) and distillations nine (17 or so lines), ten (twelve or so) and eleven (nine or so).

How to Use the Goldlist Method – Summary

- Grab a notebook and write there 25 words which interest you.

- After at least 2 weeks check if you remember them and discard 30% of all the words. The rest of the words becomes a part of the second “distillation”

- Keep on repeating the same process over and over again. The only thing that changes is that the older “distillations” get rewritten to other notebooks.

The Goldlist Method – Claims

Photo by Bookblock on Unsplash

The author of the Goldlist method maintains that:

- The method allows you to retain up to thirty percent of the words in your long-term memory.

- It is also claimed that the process circumvents your short-term memory – you are expected to make no conscious effort to remember words. Thanks to this the information will be retained in your long-term memory.

The Goldlist Method – A Scientific Critique

1. The Goldlist Method doesn’t circumvent short-term memory

One of the big claims of the Goldlist method is that it is able to circumvent your short-term memory. Somehow, thanks to it, you are able to place all the information straight in your long-term memory.

Is it possible? Not really. I have noticed that 99% of claims of this kind come from people who have never had much to do with the science of memory. That’s why let’s go briefly through what is required to “remember”.

According to the author of the Goldlist method, David James:

” [[ … ]] we are alternating in and out of these two systems the whole time, we switch ourselves into short-term mode by thinking about memorising and switch out of it by forgetting about memorising.”

Unfortunately, this is a bunch of hooey. This is what the actual science has to say about memorization.

The working memory consolidation

In order to memorize a piece of information, you have to store it in your short-term memory.

This process is initiated by allocating your attention to the stimuli you want to remember.

In other words, initiation of consolidation is under conscious control and requires the use of central attention. The mere fact of looking at a piece of paper and reading/writing words activates it.

Any stimuli that capture attention because of their intrinsic emotional salience appear to be consolidated into memory even when there is no task requirement to do so.

Next, the items you learn undergo working memory consolidation.

Working memory consolidation refers to the: transformation of transient sensory input into a stable memory representation that can be manipulated and recalled after a delay.

Contrary to what the creator of the Goldlist method believes, after this process is complete, be it 2 weeks or more, the short-term memories are not gone. They are simply not easily accessible.

Our brains make two copies of each memory in the moment they are formed. One is filed away in the hippocampus, the center of short-term memories, while the other is stored in cortex, where our long-term memories reside.

You probably have experienced this phenomenon yourself many times. You learned something in the past. Then, after some years, you took it up again and were able to regain your ability relatively quickly. It was possible because your memories were still there. They just became “neuronally disconnected” and thus inaccessible.

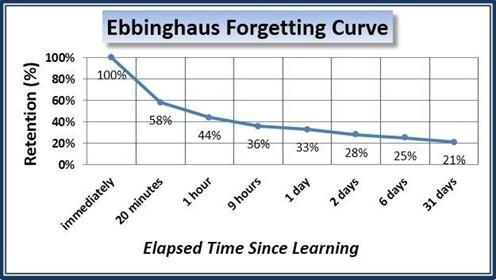

The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve

There is one more proof that shows clearly that the method doesn’t circumvent short-term memory. The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve shows us how fast the incoherent information is forgotten.

What we mean by incoherent is that this is not the information which you can associate with your background knowledge.

This is very often the case when you learn a new language or when you’re at a lower intermediate level.

What’s more, the Ebbinghaus curve’s numbers are based on the assumption that the learned material :

- means nothing to you

- has no relevance to your life

- has no emotional load and meaning for you

On the curve, you can see that if you memorize information now and try to recall after 14 days, you will be able to retrieve about 21-23% of the previously memorized knowledge. Mind you that this is the knowledge that is incoherent, bears no emotional load and means nothing to you.

What happens when you start manually writing down words which interest you or when you are able to establish some connection between them and your life? Well, this number can definitely go up.

Keep in mind that your recall rate will also be affected by:

- frequency of occurrence

- prior vocabulary knowledge

- cognateness.

Advanced language learners can get away with more

Since most advanced language learners have a benefit of possessing broader linguistic background knowledge, they can get away with using subpar learning strategies. Their long-term memory modulates short-term memory and thus decreases the overall cognitive load.

Is there anything nothing magical about the Goldlist method and the number “30”?

Nope. It follows very precisely the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve which takes into account your short-term memory. Sometimes this number will be higher, sometimes it will be lower depending on your choice of words.

You can check it yourself how low this number can get. Simply choose a language that is from a different linguistic family than the ones you already know. Track your progress and see how this number inevitably goes down.

The Goldlist Method is just a spaced repetition method with bigger intervals. That makes it less effective than most spaced repetition program right off the bat.

2. The Goldlist Method is impractical and time-consuming

Relatively high activation energy and time-consuming

One of the most important concepts in productivity is the activation energy.

The activation energy is the amount of energy needed to start conducting a given activity.

Even though the Goldlist Method has initially the low activation energy, it starts growing considerably with each and every distillation. Having to carry with you a couple of A4 notebooks seems also very impractical to me.

Limited usefulness vocabulary-wise

However, the biggest problem I have with this method in this department is that it suggests I only learn words I am interested in. There are hundreds of situations where one has to learn words that they are not interested in.

Good learning methods should work for any kind of vocabulary.s

And they should work particularly well for the vocabulary you’re interested in.

3. The Goldlist Method is inflexible

Photo by Steve Johnson on Unsplash

This is one of the methods which collapse under their own weight i.e. it’s inflexible. The Goldlist method suggests that you learn vocabulary in 25-word batches.

If I need to master a language quickly and I want to learn at least 40-50 words per day? After 10 days I will be forced to go through 20 distillations. After one month this number will start hitting insane heights. More and more of my attention will be required to keep up with all the reviews. This seems very off-putting.

Another important quality of effective learning methods is that they should automate the learning process. The method which necessitates more and more conscious decisions on your part the more you want to learn simply doesn’t fit the bill.

4. Lack of context

The enormous red flag for any language learning method is the exclusion of context from the learning process.

Simply repeating information in a mindless manner is called passive rehearsal. Many years ago it was actually proven that passive rehearsal has little effect on whether or not information is later recalled from the long-term memory (Craik & Watkins, 1973).

This is just the first problem with the lack of context.

The other one is that almost all the knowledge you possess is activated contextually. If there is no context, it will be extremely difficult for you to retrieve a word when you need it.

In other words – you will remember the information but you will have a hard time using it in a conversation.

As a result, soon enough you will forget a word because there will be no network of other information holding it in your head.

5. The Goldlist Method is detached from reality

The problem with the Goldlist Method is encapsulated in a famous adage used by Marines:

‘Train as you fight, fight as you train’

I can’t stress enough how important these words are.

Always try to train for reality in a manner that mimics the unpredictability and conditions of real life. Anything else than that is simply a filler. A waste of time. It gives you this warm feeling inside, “I have done my job for today”, but it doesn’t deliver results.

Tell me, is rewriting words from one notebook to another actually close to using your target language?

6. Lack of retention intention

Another elementary mistake that we tend to make way too often when we fail to retain a word is actually not trying at all to memorize something.

You see, everything starts with a retention intention.

This fact is even reflected in the simplified model of acquiring information:

- Retention intention

- Encoding

- Storage

- Retrieval

A retention intention sets the stage for good remembering. It is a conscious commitment to acquire a memory and a plan for holding on to it. As soon as you commit to a memory goal, attention locks on to what you want to remember.

This is how attention works—it serves the goal of the moment. And the stronger the motivation for the goal, the more laserlike attention becomes and the greater its memory benefits.

In other words, you can watch as many TV series and read as many books as you like. It will still have almost zero effect if you don’t try to memorize the things you don’t know. The same goes for the Goldlist method.

A key feature of a retention intention is the plan for holding on to the material. It might be as simple as rehearsing the memory, or it might involve one of the memory strategies described later. Whatever the plan, when you are clear about how you intend to retain the material, it is more likely you will actually carry out the plan, and this can make all the difference between a weak and strong memory.

7. Lack of encoding

Take a peek once again at the simplified model of acquiring information.

- Retention intention

- Encoding

- Storage

- Retrieval

What you can see is that the second most important part of the process of memorization is encoding.

Encoding is any attempt to manipulate the information you are trying to memorize in order to remember it better.

Shallow and deep encoding.

Encoding can be further divided into shallow and deep encoding.

In the world of language learning, deep encoding is nothing more than creating sentences with the words you intend to memorize. In other words, it’s creating contexts for the items you want to learn.

Shadow encoding encompasses almost everything else. Counting vowels, writing down the said items and so on.

Deep encoding is the fastest and the most certain way of memorizing information and maximizing your chances of retrieving it.

If you skip encoding, like the GoldList method does, you immediately revert to mindless repetitions of words (i.e. passive rehearsal).

And we all know how it ends.

Mindless repetition of words has almost zero effect on your learning. If you want to increase your chances of memorizing them permanently you need to use the new words actively in a task (Laufer & Hulstijn (2001:14).

To be honest, I could add some more mistakes which this method perpetuates. However, I think enough is enough – I think I have pointed out all the most glaring ones.

Read more about factors affecting word difficulty i.e., what kills your learning progress.

The Goldlist Method – Potential Advantages

There are two things I like about the Goldlist method

- It gives you a system which you can follow. This is certainly the foundation of any effective learning.

- It jogs your motor memory by making you write words.

That’s it.

The Goldlist Method – Suggested Modifications

The Goldlist method is too flawed to fix it in a considerable manner but let me offer you this suggestion.

Instead of rewriting words, start building sentences with them for every distillation.

This way you will incorporate some deep encoding into your learning process. You should see the difference progress-wise almost immediately.

The Goldlist Method – The Overall Assessment

There is no point in beating around the bush – this is one of the worst learning methods I have ever encountered. It violates almost every major memory principle. If you were contemplating using it – just don’t.

If you have nothing against using apps and programs to learn, I would suggest you start your language learning journey with ANKI.

Here are two case studies which will show you how to do it

- How to learn Finnish Fast – from scratch to a B1 level in 3 months

- How To Learn German From Scratch To a B2 Level In 5 Months: A Case Study

The Goldlist Method – Summary

The Goldlist method is one of the best examples of something I have been saying for years – anyone can come up with a learning method. Sometimes it’s enough to sprinkle it with some scientific half-truths to convince thousands of people to try it.

My opinion is this – you’re much better off using many other methods. This is one of the few which seems to be violating almost all known memory principles.

Done reading? Time to learn!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created 30 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go.

Great, if you enjoy it then keep on using it 🙂 Thank you and good luck with your learning!

Hi Devon!

Thank you for your comments. Some good points!

However, there are no contradictory statements here. STS like ANKI sucks as well when used inappropriately. I have never claimed anything else.

https://universeofmemory.com/spaced-repetition-apps-dont-work/

Once you apply proper strategies within ANKI, you will learn fast. they will all eliminate problems with encoding and context, and such.

As for polyglots, as well-intentioned as they are, their advice won’t work most of the time for less advanced language learners:

https://universeofmemory.com/polyglot-tips-advice-strategies/ .

As for quick learning, a couple of months from scratch to a C1 level is extremely fast for almost anyone! So I am not sure what the problem with that statement is 🙂

Have a good one!

Czyli rozumiem, ze artykul ze strony Gareth’a jest zupelnie niezgodny z prawda? Mam szczere checi i robie to za darmo od lat. To ze w procesie dostal Pan rykoszetem i Pana ego nie moze tego zniesc jest ewidentnie Pana problemem.

Wersja, jak zapewne Pan wie, została zaczerpnieta ze strony How To Get FLuent, gdzie wyraznie zaznaczone jest, ze zatwierdzil ja Pan i wniosl do niej poprawki, wiec nie bardzo rozumiem skad rzekome nieporozumienie. Nie bardzo rozumiem, czemu mam robic Panu grzecznosc? Stworzyl Pan metode i aktywnie ja promuje. Jesli ma Pan odwage zbierac pochwaly to i powinien Pan sie liczyc z potencjalna krytyka. Nie bardzo wiem, co ma grzecznosc do tego. Nigdzie nie atakowalem, i do tej pory nie atakuje Pana osoby lecz metode, ktora jest po prostu zla. Pan przedstawia swoje argumenty, ja swoje. Koniec koncow artykul nie jest ani dla mnie, ani dla Pana, lecz dla czytelnikow. To czy odniesie sie Pan do krytki to Pana sprawa. Ewidentnie meczy to Pana bardziej niz mnie szczegolnie zwazywszy na goraczkowe sprawdzanie moich profili na mediach spolecznosciowych.

A argument a propos tego, ze ja sprzedaje produkt jest tak trafiony, jak oskarzanie piekarza, ze kasuje za chleb , kiedy Pan za darmo piecze go ze starych skarpetek. Pozdrawiam!

“This is nonsense. The graph shows the effects of memory on items which have NOT been reviewed. Even I, who clearly know nothing about memory, can understand that.” “There is no optimization in the Ebbinghaus curve. It merely shows the rate of decay of memories if there is no review at all.”

I am really happy that you have written this 🙂 You see, I though to myself that even though you clearly know very little about memory, you won’t admit it so it’s enough that I don’t give you some information and with very little time you should make yourself look silly. I didn’t have to wait long. Yes, there is optimization in the Ebbinghaus’ curve. Algorithms in programs like ANKI are based on so-called critical points from this curve. So why would anyone want to go back to reviewing it after 1 day, 3 days, 1 week and then 2 weeks? Because that prevents the decay of memory traces. But you obviously didn’t know this, right? Once again, there are over 120 studies which confirm it. And yet, you’re standing here waving your hands and screaming “it’s silly!”. Yeah, science is indeed silly. Please take a look at the following graph: https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3314994/Imported_Blog_Media/ebbinghaus-diagram.png?t=1532699733218 . It shows how reviewing words after 1, 3 and so on days affects memory retention.

2. “the optimization mechanism of the Ebbinghaus’ curve doesn’t work if you use the mechanism called passive rehearsal to learn.”

Ugh. I am pretty sure you see this definition for the very first time so I will help you with it. I will also simplify it for you: Passive rehearsal is simply a mindless act of rattling off a cluster of information. There is no encoding and most of the time, there is no context. And here is some research 70’s proving that passive rehearsal has little effect on whether or not information is later recalled from the long-term memory (Craik & Watkins, 1973). Even if you optimize your repetitions.

Next time you decide to answer, please answer these question because you don’t address them anywhere – where is the element of encoding in this method?

3. Once again, please educate yourself. I don’t have to take your word for it. I read 30+ memory studies per month. Here is an entire article about writing: https://www.universeofmemory.com/writing-or-speaking/

Writing gives SOME memory benefits. So does chewing gum. Or looking at trees. Or changing the color of light while learning. There is research backing memory benefits of all these things. What you didn’t understand from this article is that only deep encoding guarantees efficient, fast and long-term learning. Writing is NOT deep encoding. It’s shallow as heck.

Once again – where is the element of deep encoding in this method? If you want to defend do it properly.

One thing is definitely true – if you believe this statement to be true, it is true FOR YOU. It is definitely not true for me. My experience is that the best language method is the one which allows you to progress the fastest. Because of the results of your work are the best possible motivator. If you think that learning a language for 4 years instead of 1 is better for you because you’re having fun then go ahead. It’s your life and it’s your time. I can tell you this, to contrast your opinion, I specialize in rapid skills acquisition. People come to me to learn fast. And I have never had even one person who wasn’t extremely motivated to learn more after discovering that they can start having basic conversations after a couple of weeks.

Please look at my other comments – I don’t think that the typical use of SRS programs is effective and I fully understand why so many people have problems using them. The way I usually put it is – the algorithms are close to perfect, it’s what you do with these algorithms that really counts. Thank you for your comment!

I fully agree with you – programs like ANKI and memrise and so on don’t work well. But there is a reason for that. Most people who use the use the learning strategy approach called passive rehearsal. It is simply a mindless act of rattling off a cluster of information. Think about it as trying to memorize a phone number by simply repeating it in your mind. Many years ago it was actually proven that passive rehearsal has little effect on whether or not information is later recalled from the long-term memory (Craik & Watkins, 1973).

So to sum up – the programs like these won’t work if you don’t understand how to use them properly and what is necessary to create permanent memory traces.

It’s extremely easy to find people who didn’t find any success using this method. The more interesting question is – why do people find success using it. My guess would be that it provides some structure which a lot of people lack in their language learning. What’s more, we get to another question – what does a person mean when they say that they learn vocabulary successfully thanks to this method? For most people, there is just one criterium for this – recalling words in a relevant context. If you use the method which is deprived of the contextual element, you will never achieve it.

As for ANKi and Memrise, people who have failed to find success with these methods did so because they don’t understand that the most important part of this program is what you do with the algorithms, not the algorithms themselves. We have known since 70’s that so-called passive rehearsal is useless for long-term retention, yet 99% of people use these programs exactly like that.

Thank you for your comment, Andre. How have you learned previously and what is your measure of success vocabulary-wise?

Thank you for your comment, Michelle. Unfortunately, even we factor in everything you have said so far, the method simply loses with even the simplest of SRS programs. With ANKI / Memrise or any kind of program of this kind, you can automate the learning of all the words you want but you are not BURDENED with remembering about all the impending reviews. It would even be much better to use SRS program like his: every time a word pops up, you write down a sentence with it. Bam. The entire process is simplified.

Very interesting comment! Thank you, Tom! Also, your modifications are spot on. That definitely should make this method more useful 🙂