Forgetting as a Form of Feedback – How To Use It To Remember Better

Forgetting is as integral to our lives as it is disliked. It takes many forms - from the nastiest ones, i.e. neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. Alzheimer's), to relatively innocent ones (why am I standing in front of the open refrigerator again?!)

No wonder we treat this phenomenon as our worst enemy. After all, it robs you of the fruits of your work. You have put so much work into acquiring a given skill, and after a couple of months not much is left in your head. As depressing as it all might seem, I would like to show you a different perspective.

What if forgetting is not your opponent but your ally?

Your brain is actively working to make you forget most of the things you've come into contact with. It is the most sophisticated spam filter in the world. This process allows you to focus on the most important information. In other words,

forgetting is one of the best forms of feedback.

It took me many years to understand this simple truth. It was also a turning point for me, which completely changed the memory systems I created at that time. Since, as far as I know, this concept is not widely discussed, I hope this article will be a sort of "memory awakening" for you.

What Is the Purpose of Memory?

Many people believe that the purpose of memory is to store information as accurately as possible. I think this is an erroneous perspective.

Memory serves to guide and optimize decision-making by sticking only to meaningful and valuable information.

I could describe a lot of memory processes that take place during the stage of encoding or information retrieval. Still, I think it's better to focus on a very logical and practical example.

Optimization of decision-making processes as exemplified by crossing the street

Think for a moment how much information you need to safely walk from one side of the street to the other.

While performing this activity, do you analyze:

Of course not.

Too much irrelevant information is detrimental to a given decision-making process.

If you really had to take into account all this information, it would take you forever to make any decision at all. In other words, the process would not be optimal, also energy-wise.

Thus, it is much easier to focus on activities such as:

As you can see, a handful of relevant information can be more valuable to the brain than a ton of meaningless data. However, we shouldn't forget that it doesn't make sense to remember much—quite the contrary. The trick is to combine the memorized information into meaningful scripts that can be activated in a given situation.

In the example above, a type of surface is almost certainly a useless piece of information. Nevertheless, if our decision-making process required making sure that we can do a dangerous stunt on the said surface, it would be one of the first factors that should be taken into consideration.

What Kind of Information Is Meaningful To Your Brain?

Another question we have to answer is what information the brain perceives as valuable, and what information is the equivalent of food scraps at the bottom of the dishwasher.

In simple terms, information must meet two main criteria to be considered valuable:

I will discuss them in more detail later in this article. At the moment, it is worth looking at how slowly we forget information when the above two criteria are met.

Almost Complete Elimination of Forgetting

Problems with research on memory

One of the big problems that plague most of the memory studies is that they are often detached from reality. The overwhelming majority of them are carried out in laboratories. I know what you are thinking. Why would that be a disadvantage?

Laboratories are artificial creations which, according to the rules of the scientific method, try to limit the number of variables that affect the tested value as much as possible. It sounds nice until we realize that our memory does not work in a vacuum. Hundreds of stimuli and information constantly flood our minds. One should not try to artificially separate them from the process of memorizing and retrieving data.

The effect is that most such studies come to conclusions that are as out of touch with reality as a team of Marvel superheroes from a nearby asylum.

What's even worse is that there are quite a few people who accept this nonsense uncritically. I often hear some strange websites or YT channels saying that "in this or that study, scientists proved (sic!) that if you imagine that you have an orange on the top of your head, your ability to remember and concentrate will increase by 15%".

I wish it were an anecdote, but the video had over 100k views and lots of positive comments at the time. In my mind's eye, I could almost see 20,000 people sitting with their eyes rolled over and the face of a constipated walrus wondering why memorizing books didn't get any easier.

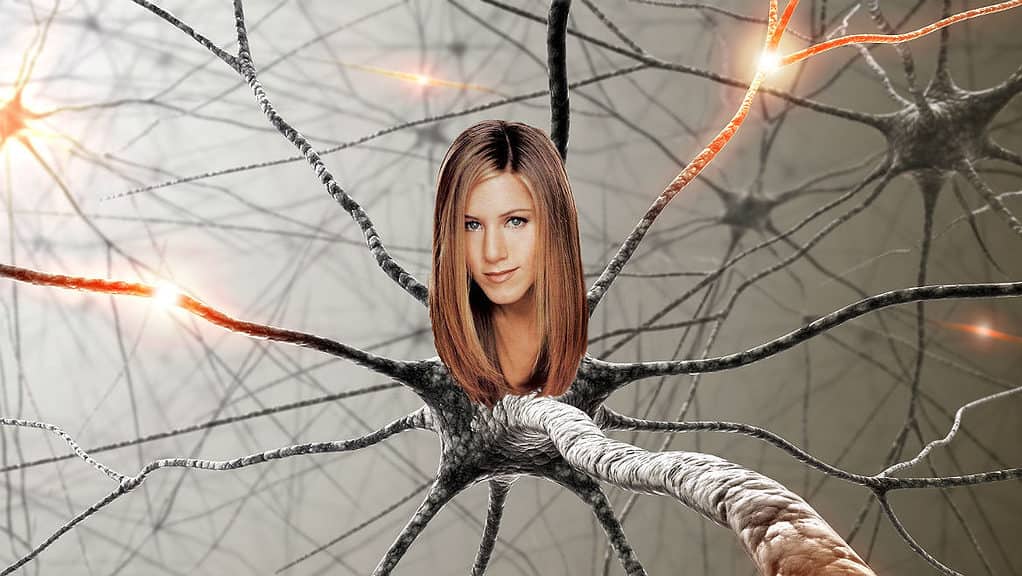

Forgetting names - Bahrick's and Wittlinger's research

Bahrick is one of my favorite memory researchers. He was one of the first scientists to insist that research of this kind be carried out outside the laboratory, despite the difficulties it poses.

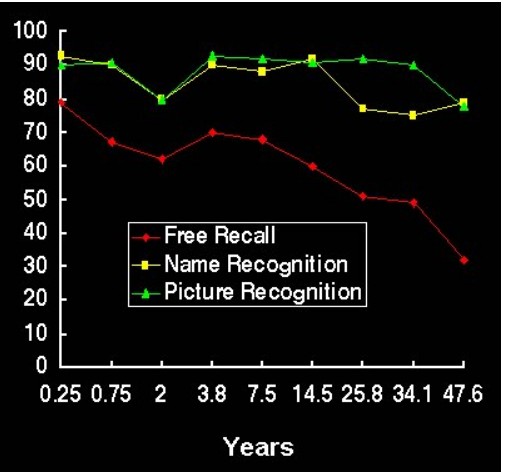

One of his groundbreaking works, which he did in 1975 with Wittlinger, is about remembering the names and faces of high school friends over many years. The study lasted 50 years (!!!), and it showed for many years after graduating from high school, the process of forgetting this information occurred only slightly. Although, as always, the active recall was the first to go.

You can conduct this experiment virtually. Assuming a minimum of 10 years has passed since you have graduated from high school, check if you can still remember everyone in your class? I know I certainly didn't have almost any problems with it.

How to explain the almost complete absence of forgetting over a long period?

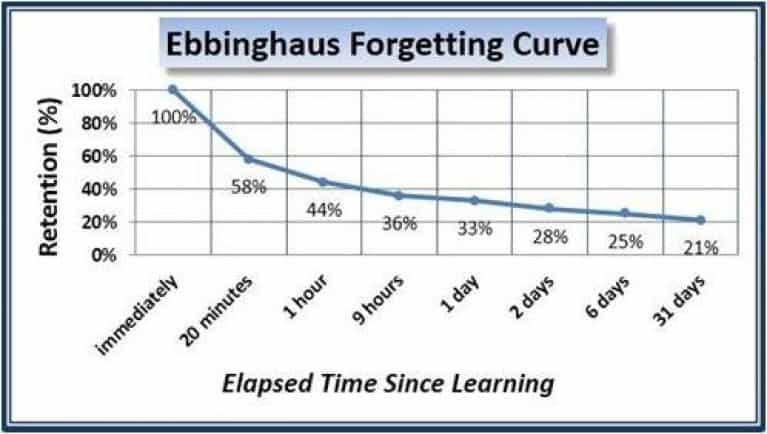

In one of my past articles, I mentioned the Ebbinghaus curve:

Notice how huge the difference in retention (i.e., keeping the information in your head) is between Bahrick's and Ebbinghaus's experiment. Even after 7 years, the retention of names was higher than the retention of meaningless knowledge presented by the Ebbinghaus curve after 20 minutes.

The explanation for this phenomenon is based on many elements.

1. High frequency of repetitions

Note that the contact with first and last names in high school is extremely common, be it during the roll call or the regular socialization with your peers. What's more, almost all children are forced continuously to retrieve this knowledge. It would be difficult to get through high school only by yelling, "Hey you!"

2. Relevance of the information

Ebbinghaus tested the information decay by memorizing nonsense letter clusters. Bahrick, on the other hand, demonstrated how we absorb vital information in the real world.

It is worth mentioning that the relevance of information automatically means one more thing - emotional load. It doesn't matter if it's positive or negative. It is an inherent factor modulating your ability to remember.

The meaningfulness of the information is a very personal and individual thing. Two different people may perceive the same facts as useless or vital. It is reflected in another one of Bahrick's (1984) studies, that showed that college professors have difficulties with remembering their students' name.

Can you see that contrast? Of course, one might argue that the frequency of information, in this case, is much lower. However, in my opinion, the decisive factor here is the indifference of lecturers. Most students are as important to them as half-dried pigeon carrion on the side of the road.

Of course, we could name more factors that contributed to the almost complete absence of forgetting in the first study. However, I think that the ones mentioned above are the most important.

Forgetting as a Form of Feedback, I.e. What Information Does It Provide You With?

The example above does not seem to be fully related to subjects such as physics, foreign languages or medicine. Regardless, I hope it convinced you of one thing - the frequency and relevance of information are among the most critical factors affecting your ability to remember information.

Thus, from now on, I would like you to change your mind about the phenomenon of forgetting. Don't see it as something negative.

Treat forgetting as the best possible form of feedback.

If you can't keep information in your head, your brain is trying to subtly say, "Hey buddy! Don't even try to make me remember this string of numbers. I don't know; I don't understand, I don't care. When are we going to do something exciting like tap dancing in banana peel shoes?

Whenever you cannot recall information, you should ask yourself, "How can I modify it so that it makes more sense to my brain?"

Forgetting as a Form of Feedback - Three Main Takeaways

1. Too little interaction with the information

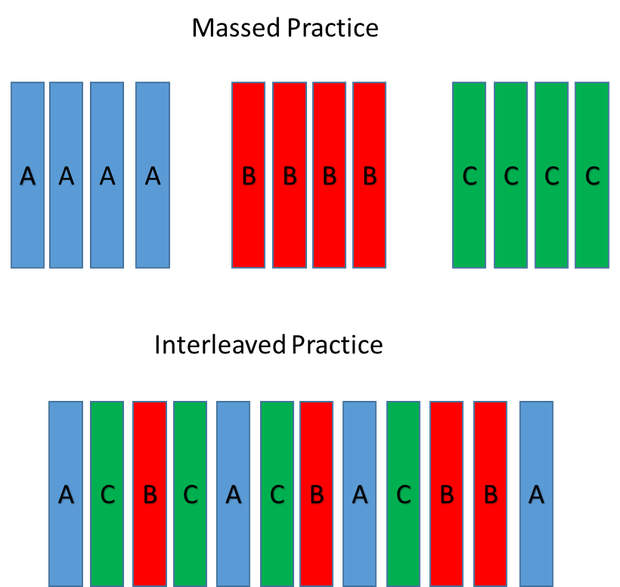

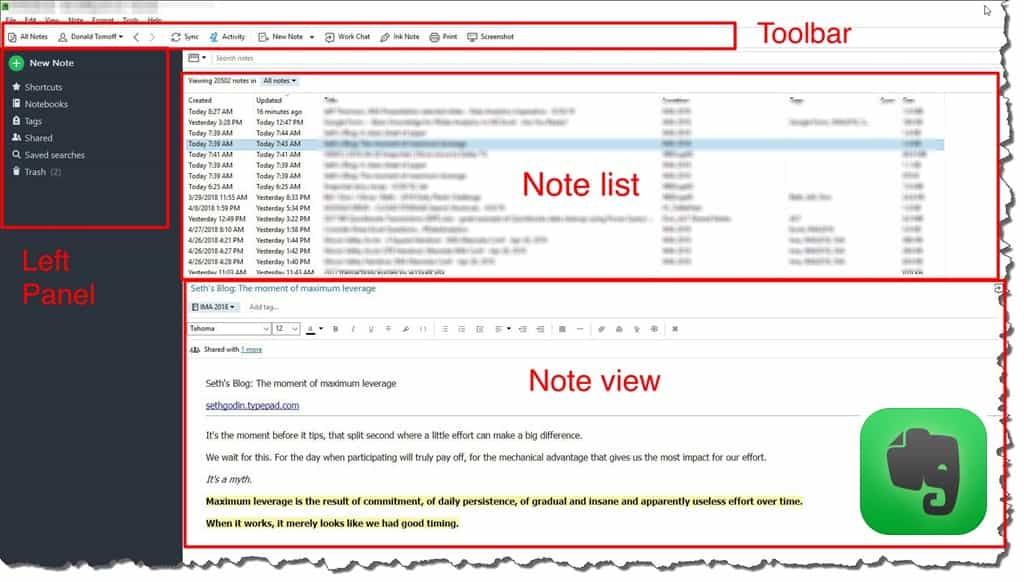

Consider whether you should increase the frequency of a given element. If you use programs like ANKI, it happens organically to some degree.

2. No connection between the element and your background knowledge

Your brain is a very practical sponge. If it finds no connection between an item and the rest of the information you have in mind, it considers that item to be irrelevant. Thus, this information is forgotten very quickly (see Ebbinghaus forgetting curve).

If you want to remember a given piece of information, there is nothing to prevent more than one flashcard from encoding a given word or concept.

3. Lack of the relevance of the information

The relevance of information always means one thing - emotional load. It is the basis of the so-called affective learning that is related to feelings and emotions.

If you are trying to learn information that has nothing to do with your life, it will not evoke any feelings in you either.

Think of it as a date, if your potential partner sparks as much passion in you as the thrilling acting of Kristen Stewart, will you remember it? I doubt it. You come home, douse yourself with bleach, you disinfect yourself from the inside and life goes on. For the same reason, we pay attention to items that stand out - they simply spur more emotions.

You are the one who is supposed to find the reasons why the information is relevant and meaningful.

The enormous mistake people make while learning is waiting until this magical connection between some abstract concept and real life materializes itself out of thin air. Nothing could be more wrong.

If you want to learn quickly and effectively, you have to look for such connections yourself. Think about how many thousands of practical examples of different types of concepts were shown to you at school. They ranged from history, through physics to economics. Now think how much of it honestly is still kicking around in your brain.

Effective learning is measured by the amount of effort you put into the information encoding process, not by time.

If I chew an exquisite dish for you and spit this slimy mass onto a silver tray, you won't probably find it appetizing. Your brain reacts the same to the information that someone else has digested.

Of course, finding relevance can also be a natural process. Remembering all the symptoms of diabetes doesn't seem like a significant thing. You need more room in your head for more important things like memorizing all names of all the Pokemon.

However, do you think that something would change in your head if your spouse were diagnosed with this disease? Without a doubt. You would immediately begin to absorb this knowledge and remember it well for a long time. This is the power of the relevance of information.

Forgetting as a Form of Feedback - Summary

Forgetting is stigmatized nowadays with a passion that characterizes naturopaths promoting coffee enemas. However, this is a short-sighted approach.

The inability to recall the information in question is nothing more than your brain, saying that it doesn't care.

Although there are many forms of feedback, hardly any of them is as valuable to adults as forgetting. After all, it does require teachers or coaches. A program such as ANKI and a bit of introspection is enough.

Done reading? Time to learn!

Reading articles online is a great way to expand your knowledge. However, the sad thing is that after barely 1 day, we tend to forget most of the things we have read.

I am on the mission to change it. I have created over 19 flashcards that you can download to truly learn information from this article. It’s enough to download ANKI, and you’re good to go. This way, you will be able to speed up your learning in a more impactful way.